The Light Comes from Within: the Jewish Spirit of Linda McCartney. An Essay

In 1989, when she published her first vegetarian cookbook, Linda McCartney’s life was already full of milestones. Yes, she was married to a Beatle and carried his iconic last name—but beyond that, Linda was a woman who had harnessed the social upheavals of the 1960s to forge her own personal revolution. She helped redefine long-standing norms in Western society—gender roles, the fusion of disparate worlds (like bringing domestic life into the rock ‘n’ roll scene), and dietary habits. Linda Eastman—her birth name—deserves far more recognition than she typically receives.

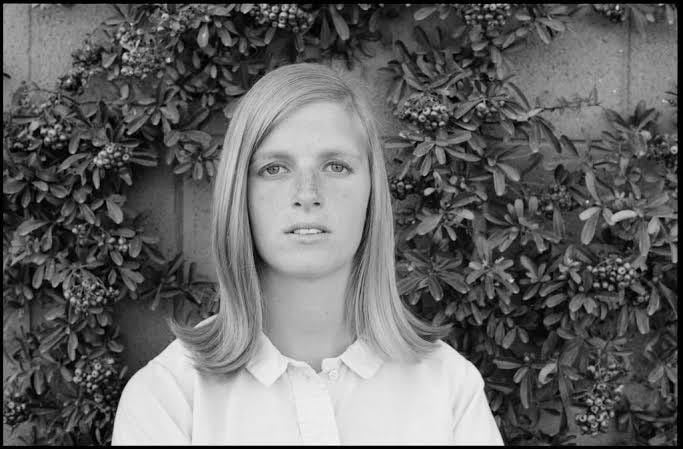

She was born in Manhattan on September 24, 1941, to a family with German-Jewish heritage on her mother’s side (Louise Sara Lindner) and Belarusian-Jewish roots on her father’s (Leopold “Lee” Vail Epstein). This heritage, though not an obvious influence on her life or work, is what I intend to explore in this piece. As Nathan Abrams said—while discussing Stanley Kubrick’s similar background—a “hidden substrate” can be found in the work of people from Jewish lineage. If you look closely, through the right lens, there is a profound Jewish undercurrent in Linda McCartney’s work, activism, and family life. It wasn’t accidental when her daughter, Stella McCartney, identified as Jewish in a 2002 interview with British Glamour. “I don’t live and breathe religion,” she added—but the identification was sincere and valid according to halakha, traditional Jewish law. Let’s take it step by step.

Linda McCartney was the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who came to America during the waves of migration between the 19th and 20th centuries. Her maternal grandfather, Max J. Lindner, made a fortune in the textile business in Cleveland, Ohio. Her father, Lee Epstein, trained as a lawyer and built a career in the entertainment industry, representing big names like bandleader Tommy Dorsey, composers Jack Lawrence and Harold Arlen, and groundbreaking abstract expressionist painters Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko.

Lee eventually changed his surname to Eastman to pass as Anglo-Saxon and to hide, at least partially, his Jewish identity. Despite working in a field where many Jews had excelled, his idea of success involved suppressing that part of himself and his family. His motto was, “Think Yiddish, look British.” It wasn’t an original idea—Jewish assimilation was an inescapable part of modernity. Persistent antisemitism on one hand, and the promise of personal advancement after the Enlightenment and the Emancipation on the other, led many Jews to deny or conceal their identity. The Eastmans were just one more family whose success seemed to confirm that the strategy had worked. With their English manners and polish, they integrated into the American WASP world with relative ease. Perhaps Linda’s earliest instinctive rebellion may have been against this very assimilation.

She had a privileged upbringing, surrounded by a sophisticated jet set of artists, creatives, and people involved in politics and law. The song “Linda” by Buddy Clark (1947) was allegedly written by Jack Lawrence at her father’s request, specifically for her; the surf duo Jan and Dean re-recorded it in 1963. She attended Scarsdale High School, an elite prep school in suburban Westchester County, and graduated from Vermont College, known for its strong focus on literature and the arts. She also studied fine arts at the University of Arizona, where she discovered her love of photography. But she never finished her degree. On March 1, 1962, American Airlines Flight 1 crashed into Jamaica Bay just minutes after takeoff from New York to Los Angeles. Her mother, Louise, was on board and died along with 86 passengers and 8 crew members. In addition to the emotional blow, the tragedy left Linda with a lifelong fear of flying.

That same June, she married Joseph Melville See, a geologist and anthropologist who specialized in Native American communities. They had a daughter, Heather, born in December 1962. Linda and Joseph divorced in 1965, with Linda gaining full custody. Although the marriage didn’t last, it gave Linda two lifelong gifts beyond her daughter: a deep appreciation for nature—especially horses—and a profound love of Arizona. There’s even speculation that Melville inspired the character JoJo in Paul McCartney’s song “Get Back” (“JoJo left his home in Tucson, Arizona / For some California grass”).

To me, this turbulent period in Linda’s life was driven by the subconscious but powerful impulse to reject her father’s enforced assimilation. Though she never undertook a formal return to Judaism (teshuvah), her rebellion led her to a life filled with creativity, activism, and a reconnection—conscious or not—with parts of her Jewish identity that the Eastmans had tried to suppress. Her pursuit of freedom and openness, her instinct to challenge convention, her compassion, her parenting style, and her joyful approach to life—all stood in contrast to the formal, restrained seriousness of her father’s world. These qualities, combined with the cultural revolution of the 1960s, propelled her into a different kind of success—one her father ultimately had no choice but to support.

Linda McCartney’s Jewish identity must be understood through a nuanced lens, one that requires careful unraveling. If we strictly adhere to the halakhic definition, Linda is a Jew by law—ethnically and legally—an inheritor of the cultural lineage of an ancient people. According to Jewish law, one of the inescapable ways of being Jewish is being born to a Jewish mother. In terms of religious observance, however, her upbringing was, as has already been made clear, minimal. There’s no evidence of ties to a Jewish community, whether in her native New York or in the other places she lived.

While religious practice is not the definitive marker of Jewish identity—many Jews are secular and still belong fully to the people—there are cases, like that of the Eastman family, where abandoning religious observance appears to reflect a conscious distancing from Jewish affiliation.

To explore Linda McCartney’s Jewishness beyond halakhic parameters, we need to ask deeper questions, ones that perhaps stretch the conventional boundaries of identity and self-identification. But in Linda’s case—one of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century, thanks in part to her marriage to a Beatle—we can find numerous clues in her life and work that point to what might be called the spiritual nuances of Jewish identity.

Because identity can extend beyond technicalities—beyond being born into a Jewish family or adhering to the mitzvot, the commandments that form the foundation of Jewish religious life. In the Jewish case, identity also encompasses a shared narrative and memory: a long, sometimes winding, sometimes straight line that includes foundational stories of divine liberation, but also centuries of historical subjugation. It includes a sense of collective peoplehood, a textual tradition, ancient rituals and practices, a sense of belonging that transcends belief, and a pride rooted in endurance and transcendence.

Linda McCartney inherited a Jewish lineage marked by the Ashkenazi diaspora. Whether or not she actively embraced that legacy is another question—but the ancestral ties, voluntary or not, and the weight of Jewish history matter. In this sense, she is part of a cultural fabric, whether she consciously identified with it or not.

This is a crucial point often lost in binary understandings of identity—Jewish or not Jewish. Jewish identity is multidimensional: it ranges from the religious to the historical, the cultural to the ethnic, and allows for complex forms of identification. On one hand, it offers a broad spectrum of ways to belong; on the other, it’s also a tradition with boundaries, whose access isn’t solely determined by self-perception. So yes, there are Jews who feel and identify as Jewish despite not being religious. It’s more complicated than mere personal belief.

If we understand Judaism as peoplehood, then being Jewish is also a way of inhabiting the world—beyond theology or doctrine. It’s a series of attitudes, visions, reactions, questions. In the 20th century—the century of the Shoah, of the founding of the State of Israel—Jewishness moved from the margins to the center of world history. To be Jewish is to be a fragment of a vast mosaic, a thread in a larger tapestry, a small element in an unfolding story. One is within it, and it is within the person. A person is not merely a vessel of inherited tradition, but a conduit through which that legacy continues to flow—whether or not they actively practice the religion.

In October 1998, with the release of Wide Prairie, Linda McCartney’s musical work was canonized in a compact disc. The posthumous edition is beautifully done: beyond the radiant cover image of Linda, the CD comes in an elegant cardboard sleeve, accompanied by a fold-out poster filled with intimate, rarely seen photographs. Paul McCartney promoted the album through a pioneering webcast, and although it only reached number 127 on the UK charts, today it stands as an essential piece in any McCartney or Beatles collection.

From the title alone, Wide Prairie evokes openness and vastness—an expansive horizon that, paradoxically, feels intimate. It was a retreat for Linda and her family, but also a space of inspiration and creativity. Among fans, however—and particularly among a vocal sector of critics—there lingered a persistent idea: that Linda lacked the credentials and talent to be part of her husband’s post-Beatles band, Wings. At the heart of this criticism lies a single fact: she was his wife. At the time, gender roles were just beginning to loosen, to become more fluid. In a sense, despite having come of age in a macho, chauvinistic northern town, the Beatles became early public figures to embrace evolving gender attitudes in the latter half of the 20th century. It wasn’t just their androgyny, long hair, or their occasional open and subtle challenges to the rigid postwar establishment—it was also reflected in their personal relationships with women.

After the failures of previous relationships—failures that often stemmed from masculine attitudes and lack of emotional accountability—the two most visible Beatles, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, married women who represented a new, non-patriarchal paradigm and were, notably, not British. Yoko Ono and Linda Eastman were both independent figures with personal success born from their own merits—women who had fought their way into closed, male-dominated systems. Though both came from privileged backgrounds—Ono, the daughter of a banker, from a Japanese aristocracy fractured by World War II; Eastman, from a wealthy family of German and Belarusian Jewish immigrants who found success in pre-WWI New York—both women forged their own paths in traditionally male spaces, without abandoning normative femininity.

Critics often pounced on Linda’s voice—this had been the case since her days in Wings, where she was widely seen as nothing more than a case of rock 'n’ roll nepotism. True, Linda didn’t sing like a professional. But, as with other unconventional artists, her raw, unpolished, vulnerable voice became a mark of sincerity, of creative impulse over formal training. In contrast to Paul’s meticulously orchestrated music, her voice is a sonic mirror of her inner life—as if each note were an act of self-discovery.

Songs like “The Light Comes from Within” gain their power from the tension between fragility and strength that defines Linda’s artistic voice. Her vocals aren’t just a vehicle for words—they become a kind of performance, marked by intentional looseness, a series of expressive gestures. In this, a line can be drawn between Linda and Yoko Ono, particularly in their shared use of voice as an expressive instrument that defies conventional vocal standards. Yet while Yoko explored transgression—shaped by her background in Fluxus, the movement founded by George Maciunas that aimed to break boundaries and blur artistic categories—and ventured deep into avant-garde and academic music (even when she later turned to pop, she retained a distinctly experimental edge), Linda stayed within the realm of pop. Her language was shaped by intuition and experience—listening to early ‘60s girl groups, Jamaican reggae, American pop, and British white blues.

Where Yoko pulled Lennon into the density of a radical avant-garde, Linda allowed herself to be embraced by McCartney’s musical fluency, testing her own abilities and limits within the self-contained space of the pop song.

In Wide Prairie, the tension between public and private that defined the McCartneys' life together surfaces clearly. The privileges of fame are embraced, yet Linda also uses music to claim a personal space. It’s a quiet rebellion against being merely the wife of a former Beatle or a two-dimensional artist confined to photography—a medium dependent on technology. Through her voice—her body—Linda asserts herself as an artistic presence, weaving together a mosaic that reflects her inner world. While she cannot—and does not—escape her association with McCartney (from which she also benefits), she articulates emotional states that Wings songs rarely capture. Tracks like “Seaside Woman,” a kind of "whitewashed" reggae, might feel like Wings outtakes. But others, like “Love’s Full Glory,” are deeply personal creations that could not exist without Linda’s voice and sensibility.

Nature is a recurring motif in Wide Prairie, evoking freedom, renewal, and the cyclical rhythms of life untouched by human interference. This natural world is often contrasted with human intervention—because humans, possessing free will, must choose how and when to mediate. Some songs are told from an animal’s point of view (“Cow”), others celebrate animals as living beings in their element (“Appaloosa”), and others denounce their mistreatment and commodification in consumer society (“The White Coated Man”). These songs do not offer illusions, but present a reality filtered through an ethical lens rooted in discomfort and questioning.

For much of her life, Linda McCartney was a passionate advocate for animal rights, and by extension, for vegetarianism and alternative lifestyles grounded in the fundamental value of respect for life. Her spiritual disposition leaned toward justice and compassion. While she was not a woman of the synagogue nor a follower of kosher dietary laws, her fight for animal welfare—carried out within a framework of respect and legality—her insistence on ethical consumption, and her commitment to environmental restoration through rational action align closely with the values of tikkun olam, or “repairing the world.”

This concept, which contemporary Judaism—especially in the American Reform movement—has placed at the center of practice, often takes precedence over liturgy, ritual, and even textual study, which remain central in other branches. Linda’s alignment with this idea springs from a belief that human beings have the power to transform the world through their actions, and therefore must assume individual responsibility with far-reaching collective consequences.

Kashrut is the Jewish system of dietary laws that determines which foods are considered fit to eat. It classifies food into three main categories: meat and meat products, dairy, and parve—neutral items such as fish, eggs, or vegetables. Its core principles include the strict separation of meat and dairy, the ritual slaughter of animals (shechita), and the complete removal of blood from meat, traditionally using coarse kosher salt. Only animals that both chew the cud and have split hooves are permitted, meaning that pork, rabbit, camel, shellfish, and fish lacking fins and scales are not allowed.

There is little consensus on the rationale behind these laws, aside from their sacred traditional role. While some argue they have hygienic or health-related foundations, such explanations are neither definitive nor immune to contradiction. Others see them as mechanisms for self-discipline, maintaining a distinct identity from non-Jews, or encouraging compassion by heightening awareness of animal suffering. More modern interpretations point to ethical and sustainable consumption: by regulating what one consumes, a person makes a declaration of respect for the world through voluntary restraint.

Rabbi Ephraim Buchwald, an influential figure in contemporary Orthodox Judaism, offers another widely discussed interpretation: that the laws of kashrut were, by design, intended to discourage the consumption of meat, as many of the restrictions apply specifically to it. Theologically, it is said that in the time of Noah, humanity was vegetarian. Meat consumption was later allowed only as a concession to human weakness—and therefore, had to be carefully regulated. In this view, vegetarianism is not only permissible, but spiritually preferable.

Linda and Paul McCartney always told the same story: they were eating a lamb chop when they looked out the window and saw sheep grazing on their idyllic property. Whether the story is factual or a small personal myth doesn’t matter—it captures the essence of their stance toward eating meat. For them, abstaining wasn’t merely a matter of personal health, but of mercy and recognition of animals as sentient beings. Linda McCartney didn’t follow kashrut—at least not openly or consciously. And yet, by making a definitive personal choice, she arrived at an adjacent place. As every Jewish person knows, observant or not, a vegetarian diet is almost by default kosher.

But Linda’s choice extended well beyond the personal. In addition to writing several cookbooks—culinary arts being one of her many talents and sources of pride, as seen in Wings’ “Cook of the House”—she founded Linda McCartney Foods in 1991. At a time when being vegetarian was far more challenging than it is today (and even now it still isn’t always easy), she launched a line of frozen meat- and animal-product-free meals, helping make an ethical lifestyle more accessible to a broader public. It was tikkun olam in its fullest expression.

Linda McCartney’s love affair with reggae music and culture is as fascinating as it is little known to the general public. Listening to Wide Prairie, one can catch glimpses of this passion in tracks like “Seaside Woman” and her confident covers of “Sugartime,” “Poison Ivy,” and “Mister Sandman.” But this interest goes far beyond surface-level appreciation—it’s an obsession that deserves deeper exploration.

Linda first fell in love with reggae thanks to “Tighten Up” by The Inspirations, a Jamaican single that made waves in the UK in 1969. From that moment on, Jamaica became both a physical destination and an emotional landmark within Linda’s life map. The McCartney family visited the island many times, spending weeks immersing themselves in its music and culture, forging bonds with locals. It's no secret that themes central to reggae—even in its earliest forms—include resistance, liberation, and justice, ideas that resonate deeply with Jewish history and identity. Freedom, equality, and empowerment have been core ideals of the Jewish experience for centuries, captured most powerfully in the Book of Exodus—a foundational narrative not only in Judaism but also in early reggae and the Rastafari movement.

Rastafarianism, a religion that emerged in Jamaica, is intimately tied to reggae and contains striking parallels with Jewish thought—particularly in the central role the Hebrew Bible plays in its imagery and philosophy. Rastafari draws direct lines between African slaves during the colonial era and the Israelites in Egypt, blending Christianity, African spirituality, and Hebrew themes into a complex syncretic faith. Jamaica, as a historical crossroads between continents, was inevitably a crucible of cultural fusion: Europeans chasing fortune, Africans forced into labor, Jews fleeing the Inquisition, and Indigenous peoples all collided—sometimes violently—to create something new.

Leonard Percival Howell, considered the father of Rastafarianism, was born in Jamaica in 1898 but led a nomadic life that took him to Panama, the United States—where he spent time in Harlem and encountered Black Judaism—and back to Jamaica carrying a rich, hybrid philosophy. True civilizations are built on mixed ideas; ideas of social purity can lead to barbarism. History speaks of this.

The return to the Promised Land—Zion—as both a home and destiny is a shared pillar of both Rastafari and Judaism, as is the notion of diaspora. Like Judaism, reggae naturally blends the spiritual with the earthly, recognizing them as twin dimensions of human life in a world governed by natural law but shaped by human language—a sacred tool that forms the foundation of our relationship with the divine. Hence, the importance of the text.

Reggae also openly celebrates community and unity—ideals that sustain life in the face of oppression through collective strength. The cosmopolitan side of Linda McCartney found in a small Caribbean island a culture she admired deeply, one that mirrored aspects of her own heritage—buried under her family’s efforts at assimilation, but never erased.

A salvific vision of freedom—and the responsibility it entails—as a guiding value. The importance of community and collective identity. The possibility of redemption. The return to Zion—whether Africa or Eretz Israel—as a spiritual homeland. Rastafarianism’s incorporation of Jewish symbols such as the Star of David and the Lion of Judah, its view of Haile Selassie as a messianic figure descended from the biblical House of David, and the Exodus narrative as metaphor for exile and the yearning to return—these elements converge in a rhythm that distills all this complexity into something you can dance and sing to.

A perfect reflection of Linda McCartney’s deep and intuitive sensitivity.

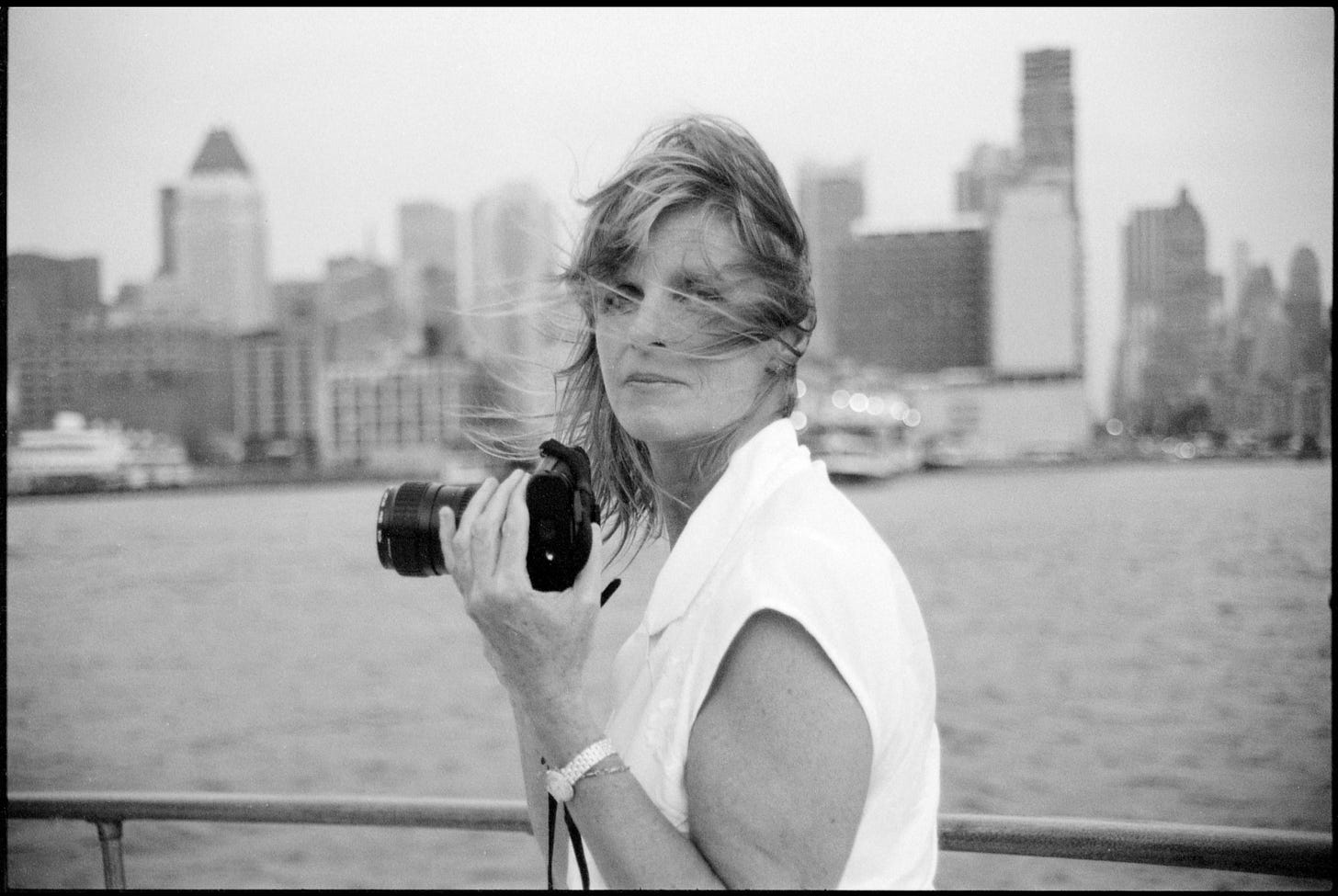

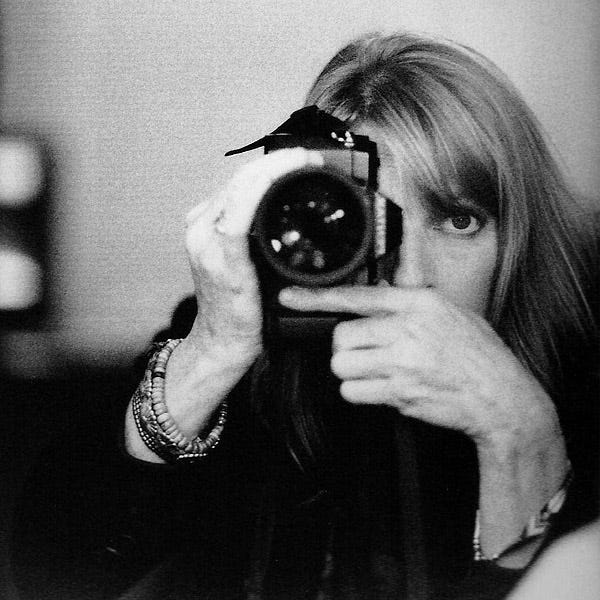

Linda McCartney’s photographic career—the work to which she devoted the most time, energy, and resources—is one of the most significant of the 20th century in its field. Beyond technical skill, her art lived in her eye: she had a gift for capturing the essence of her subjects because she treated them as people, not as objects. Her work isn’t centered on aesthetics—she takes beauty as a given. What she focuses on are gestures, postures, the quiet dignity or charm of a person or object simply existing. She didn’t rely on elaborate setups or staging. On the contrary, her photos are full of relaxed poses, spontaneous smiles, wide eyes, open mouths, hands busy with the stuff of everyday life.

Linda saw herself as a privileged witness, equipped with a kind of magical technology—an artifact that could write with light just as others write with ink, sound, or paint. She wasn’t trying to freeze moments or document reality in a traditional sense, but rather to probe what was going on in the soul of the person in front of her—to enter into a kind of dialogue with the inanimate things that, whether by human hands or nature’s design, had been created with purpose.

Perhaps the most fascinating side of her photography is the work she never intended to show: the private images, taken at home, with her children and husband, with their animals and their things. These aren’t historical records of specific events, but emotional documents—photographs that hold feelings rather than dates. Her compositions are playful, the light sometimes erratic, the focus imperfect. But more than anything, they’re acts of love—like cooking a meal and serving it to someone. She photographed the people she loved in order to preserve them, to keep them alive forever.

In her role as a mother, Linda—whether consciously or not—built a family in the Jewish tradition. It’s true that she didn’t teach them the religious rituals, didn’t emphasize the historical narrative, didn’t introduce them to traditional Jewish cuisine. But she did instill in her husband and children the value of familial cohesion—as a form of survival, and more importantly, of transcendence. She wasn’t perfect, of course. But she was always honest with her impulses. And despite everything—her liberal use of marijuana at home, the long stretches when she and Paul toured with Wings, dragging their kids and pets along regardless of school schedules (with the argument that this, too, was education—and one no classroom could offer; it would be foolish to deny there’s some truth to that)—she raised and shaped a compassionate, curious, creative clan.

I would have loved to host them all for a Passover seder.

In the end, Linda’s Jewish identity was as much what she inherited as what she lived. Her Jewish roots were part of her historical family structure—something she carried with her, even if she didn’t publicly identify with it, in large part due to her father’s rejection of their lineage, most visibly expressed in the change of the family name from Epstein to Eastman. But beyond that, Linda embodied a form of Jewish spirituality not rooted in ritual or otot—visible signs—but in a deep and internal connection to compassion, justice, and artistic expression. She was more Jewish than what meets the eye: her life reflected a commitment to making the world better, grounded in the belief that individual actions matter and shape both personal and collective destiny. To reduce her Judaism to ancestry or legal status is to deny it; in the benevolent tradition of Hillel, the work of the soul transcends into earthly life—it’s not about saving oneself, but about leaving behind a better world for future generations. That is what truly matters.

And, of course, there is the notion of imperfection. In Judaism, there are no flawless heroes—all the patriarchs and matriarchs, prophets and kings, err as human beings; the people themselves, throughout the Bible, the Talmud, and history, fail and sin again and again. Nor is there any notion that the world is complete or finished. The messianic idea is not so much that of a saint who redeems humanity, but of humanity reaching its own goal, understanding its mission, and carrying it out. It is, therefore, a compassionate philosophy that forgives error, because error is inherent to the human condition. Otherwise, there would be no need for God—or for humans.

She was married to a Beatle who still misses her after all these years. Her death in 1998, from cancer at the age of 56, is just one of the many tragedies that her family has endured. Yet she left behind a legacy far more significant than what is usually captured in the annual tributes published in newspapers and websites. Her inheritance is not only a vast collection of photographs, a handful of beautiful songs, or children who are artisans—Heather—photographers and activists—Mary—high-fashion designers—Stella—or musicians—James—all of whom, according to halachic law, are Jewish. Her contribution may seem modest, but it runs deep. If one person became more aware of compassion through her vegetarianism, if one soul sought to explore cultural roots, if a single individual had their perception transformed by a song, a photo, a statement, or a song Paul McCartney wrote for her—then the world has changed. Because every person is a universe unto themselves. That’s why in Judaism, pikuach nefesh—the principle of saving a life—is of utmost importance. Any other commandment, any restriction, can be suspended in order to uphold it.

Linda McCartney was not religious in the conventional, liturgical sense, as has been said. But she was spiritual—through certain rituals like food and music, through her relationships with her family, through her commitment to freedom. We don’t know whether she believed in God in a traditional sense, but it’s clear she had a solid faith in humanity, one that she demonstrated in her conscious construction of family and community cohesion around her. In Judaism, divinity is manifested in precisely that way—by sanctifying the smallest acts. The idea of the sacred isn’t about revelation or mysticism, but about setting something apart, about recognizing its value through its difference.

C/S.