The Beatle, the Artist, the Journalist, and the Rabbi: A Touch of Jewishness in John and Yoko's Bed-Ins, 1969

I

On March 20, 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono were married in Gibraltar, “near Spain”. The couple, who had been involved in a high-profile affair, sealed their union in an adventure befitting their status. At a time marked by the tumultuous final months of The Beatles as a group—including the Get Back project being suspended for a year and a half, money issues with their company Apple, the arrival of Allen Klein as their new manager, growing tensions within the group, and, as if that weren't enough, Paul McCartney's marriage to Linda Eastman—the Lennons finally formalized their marriage in the British colony.

Their first attempt was in Southampton, where they intended to have a ceremony aboard a ferry. Two things prevented this: Yoko's documents were incomplete and the captain was not authorized to legally officiate. The second one was in Paris, a whimsical and naively romantic idea, but the authorities denied permission, citing insufficient time spent on French soil. Peter Brown, a trusted aide at Apple, explained over the phone that as a British citizen, Lennon could fly to Gibraltar to marry. The Pillars of Hercules seemed like a perfect spot to Lennon and Ono. There, in the consulate office, official Cecil Wheeler legalized the union in a ten-minute ceremony, with they both dressed in white. The details are well-documented in "The Ballad of John and Yoko" by The Beatles.

That same day, they returned to Paris. On the 25th, they arrived in the Netherlands to begin the public part of their honeymoon: their famous Bed-Ins. Capitalizing on media attention, they decided to use this publicity to promote World Peace, their particular brand of hippie activism. Despite its naivety, it was an event that left its mark on the pop history of the '60s, which seems increasingly distant but defined the rest of the 20th century worldwide.

II

John Lennon and Yoko Ono's Bed-Ins had a pair of touches of Judaism that added color to an already flamboyant series of events. In Amsterdam, the couple jumped into a bed at the Hilton Hotel from March 25 to 31, 1969. During those days, they received journalists from around the world who initially expected something sordid, sexy and sensationalist. Instead, the Beatle and the conceptual artist spent their time lecturing on peace, denouncing the brutality of the Vietnam War, and chanting slogans (“Bed peace! Hair peace!”). Their campaign had all the hallmarks of advertising, and indeed, there was intentionality in it: John and Yoko wanted to "sell" peace as a product that would outweigh the war item that the West had bought without question.

On one of those Dutch days, Israeli journalist Akiva Nof appeared in the presidential suite, room 702, John and Yoko's quarters. They had set "office hours" from 9 AM to 9 PM, with breaks for meals, hydration, and bathroom visits. Nof, who was a student in the Netherlands at the time, freelanced for Radio Israel (or Kol Yisrael, "the Voice of Israel," as it was also known). He arrived outside of visiting hours when John was alone: Yoko had stepped out for some undisclosed reason. The musician’s entourage prevented him from entering, but after a second attempt, John himself requested his entry. Nof found himself inside the room with a relaxed Beatle eager to talk.

He asked the standard questions, they talked about peace and love. At one point, Nof —with his portable recorder on—asked John if he knew any Israeli songs, to which Lennon, somewhat embarrassed, replied that he only knew "Hava Nagila," and not even that well. Lennon even briefly and awkwardly sang it. Later, he sang a snippet of "I Want You (She's So Heavy)"—which was then unreleased as he pointed out—and ended with a cheerful greeting: "Hello, Israel!" Any other member of the press might have been more than satisfied, especially after sneaking in out of hours.

But Nof didn't stop there; he requested John to sing a song that the journalist himself had written to be sung by the rabbinical choir of the Israeli Army. What could be better than having the approval of a Beatle? To his surprise, Lennon happily agreed. Since it was in Hebrew, Nof wrote out a transliteration of the lyrics on paper for him, and John, guitar in hand, sang; Yoko had rejoined and provided a second voice. Fortunately, there is a recording of the moment. John sings in fluent Hebrew: "Jerusalem, we have sworn to you for eternity, we will not abandon you from here and forever."

The segment was broadcast by Kol Yisrael but remained unknown in the West until the Internet era. A gesture from John and Yoko that shows their campaign was serious and another of the many Beatles curiosities that delight enthusiasts, collectors and completists.

Akiva Nof became a member of the Knesset, the Israeli Parliament, from 1974 onwards, always in center-right positions. On two occasions, he served as a representative of Likud, the party founded by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon. He published two books of poetry (Longing for the Past and Pleasure Comes Forever) and composed several songs, including a number one in Israel, "Izevel." And, of course, in 1969 he got John Lennon to sing one of his songs.

III

A few months later, on June 1, 1969, Lennon and Ono staged another Bed-In, this time at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, Canada, rooms 1738, 1740, 1742, and 1744. The event is notorious because, in addition to the circus-like atmosphere representing these pop happenings, it was where the single "Give Peace A Chance" was recorded, Lennon's first hit outside of The Beatles. The record was credited to the Plastic Ono Band. It's a folk-pacifist anthem with a highly effective slogan, an endlessly catchy chorus, and a choir of euphoric voices singing for a cause.

It happened in Montreal because it couldn't happen in the United States: the plan was to do it in New York, but Lennon carried a legal ban due to his London charges for cannabis possession in 1968. The Lennons arrived in the Bahamas on May 24 and stayed at the Sheraton Oceanus, but the heat was too much for them. They traveled to Canada, where the Amsterdam experience was repeated to a large extent, with more journalists, more celebrities—Allen Ginsberg, Timothy and Rosemary Leary, Tommy Smothers, Petula Clark, Murray the K, and Dick Gregory peeked in—, more scandal—the American press had direct access to the event—, and more heated discussions, such as the one Lennon had with cartoonist Al Capp.

Rabbi Abraham Feinberg flew in from Toronto, drawn by John and Yoko's efforts for peace. Feinberg had a considerable career not only as a spiritual leader but also as a singer and political activist, and what the couple was doing seemed to align with what he wanted to achieve.

Feinberg was born in Ohio, United States, on September 14, 1899, to Jewish immigrants from Grinkishi, Lithuania, who arrived in America seven years earlier. His father Nathan was a rabbi and cantor; his mother, Sarah Abramson, was a housewife. The Feinbergs lived in poverty in the mining town of Bellaire and, with ten children—Abraham was the seventh—, they struggled to settle in their new place. Rabbi Abraham Feinberg did well in school, receiving family support, and early on developed a deep social consciousness from witnessing systematic racism against African Americans.

An incident that marked him was a terrible injustice against a young Black man who, fleeing from the beatings and stone-throwing of a group of locals, leapt into the Ohio River. Even there, he continued to be stoned, and drowned, probably after receiving a blow to the head. The crime was not considered such by local authorities. This incensed Feinberg. From that moment on, he fought alongside miners to form unions, defended the poor and marginalized from injustices in a town hardened by racial violence and the friction that often exists in working-class enclaves, and studied diligently to be an active agent of social change.

In 1920, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Cincinnati—working in low-paid menial jobs to save money for admission—and in 1924, he was ordained as a rabbi by the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, the oldest Jewish seminary in America and distinctly reformist; it was founded in 1875 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise.

He worked six years with communities in Niagara Falls and Wheeling, and settled in New York at Temple Israel on Park Avenue, an affluent community where he never quite fit in. In fact, in 1930 he resigned from the rabbinate, frustrated by his inability to work on social issues and feeling a spiritual void that he couldn't fill in an uninspiring environment. The most penetrating phrase from his resignation speech (which received disproportionate media coverage, even reaching European communities) was: "Organized religion is a deserted lighthouse."

After moving to France, where he studied at the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau, Feinberg briefly became Anthony Frome, a notably gentile alias for his new role as a singer. He returned to New York in 1932 and started a very popular radio program on WMCA. It was such a hit that he was hired by WOR, a powerful station with coverage extending across the northeastern United States. He sang songs in six different languages with the baritone voice of a wanderer prince who had seen it all. During this time, he lived a dandy life, far from the pious study of the Torah. But events in Europe made him change his mind.

With the rise of Nazism, he returned to the rabbinate. His desire for justice was reignited, and he dedicated his efforts once again to the creation and consolidation of communities: the Jewish doctrine of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world, became his focus from then on. He returned to New York in 1935 to Mount Neboh Temple on 79th Street. Three years later, he arrived as rabbi at Temple Emanuel in Denver. When the United States entered World War II, he volunteered as a chaplain but was rejected by the army for medical reasons.

In 1943, he arrived in Toronto at the Holy Blossom Temple, the distinguished Reform synagogue. He continued to campaign for Jews in Europe and, of course, for the unity of Jews in America and the world. In fact, during this time, he was anything but a pacifist, seeing the war as a necessary struggle against Nazi evil. After the war, he continued to lead the synagogue until 1961. His work focused on helping the underprivileged, combatting anti-Semitism, and promoting peaceful Zionism.

During the pop era of the '60s and '70s, Feinberg was a fervent activist, this time against the Vietnam War. In fact, he was in Hanoi, where he was received by Ho Chi Minh. From there, he condemned the US military's Rolling Thunder operation. He was also a staunch supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. It was at this point in his life, at the age of 69, that Feinberg fell in love with John and Yoko's pacifist campaign.

Times were turbulent in the United States. Abraham Feinberg stated his position from the outset: he publicly denounced George Wallace, the governor of Alabama and a white supremacist; he defended interracial marriage and integration; he declared the Vietnam War immoral and encouraged interfaith understanding. Although the Torah states that "just love" is not enough—contrary to what Lennon sang in '67—Feinberg always believed that it could be a perfect starting point for whatever movement that could bring society together. His activism went beyond pop protest, but he considered it a useful tool for spreading the message to more people. Some started calling him the Red Rabbi.

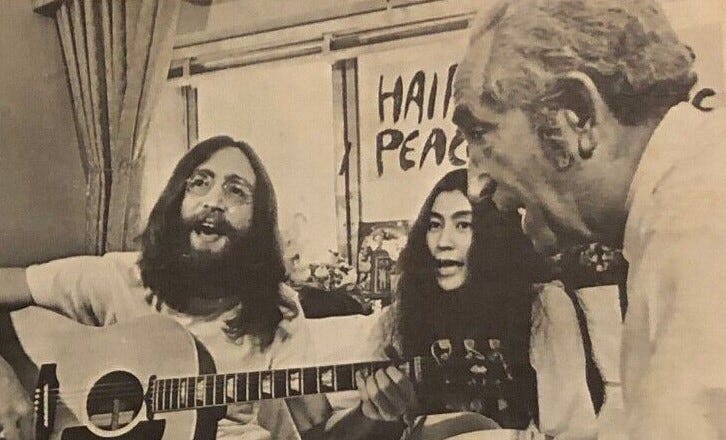

Attending the Bed-In in Montreal, then, made a lot of sense. If he could strengthen ties with these new ambassadors of peace and, moreover, explain his struggle to such powerful spokespeople as John and Yoko, he thought he could advance his program. There are not many records of their conversations, but an article in the Montreal Gazette details Feinberg's activities with the Lennons during those days.

In addition to appearing on Canadian television with John and Yoko to promote the peace campaign, the rabbi is one of the voices singing the chorus of "Give Peace A Chance" and is actually indirectly mentioned in the song ("Bishops and Fishops and Rabbis and Popeyes and bye-byes"). Rabbi Feinberg and Lennon got along very well from the start, so much so that the former almost gave the latter a dragon-handled cane that Ho Chi Minh had given him in 1967. Instead, he promised to get him a replica; it's unclear if he fulfilled that promise.

Abraham Feinberg told John Lennon about his past in music during the '30s. They talked about the rabbi's foray into secular song and the radio, but also about how he had lost touch with modern music, which he nevertheless found so meritorious. He was interested in how it had become an essential part of civil movements and the sound of a generation, and he expressed amazement about how the Beatles and the other greats of the decade had made it evolve. Before, he said, it was mere entertainment; now it was a revolution in itself.

Yoko retorted in her style. “Any sound you make is beautiful,” she said. Lennon and Feinberg tried to sing together, in harmony. The Beatle showed him his new song, "Give Peace A Chance," whose final take was done the next afternoon, recorded by local studio owner André Perry. They discussed the lyrics, in which Feinberg introduced the idea of alluding to rabbis but also bishops. They spoke about collaborating on a song together and recording it. “John Lennon and the Flaming Red Rabbi,” Feinberg suggested. That would have been nice to see and hear.

Nevertheless, John convinced the rabbi to start singing again. It wasn’t difficult. Although out of step with the militant and fast-paced pop of the time, the rabbi widely admired the conscientious and poetic lyrics of folk-rock and the classical sensitivity of the Album Era rock music.

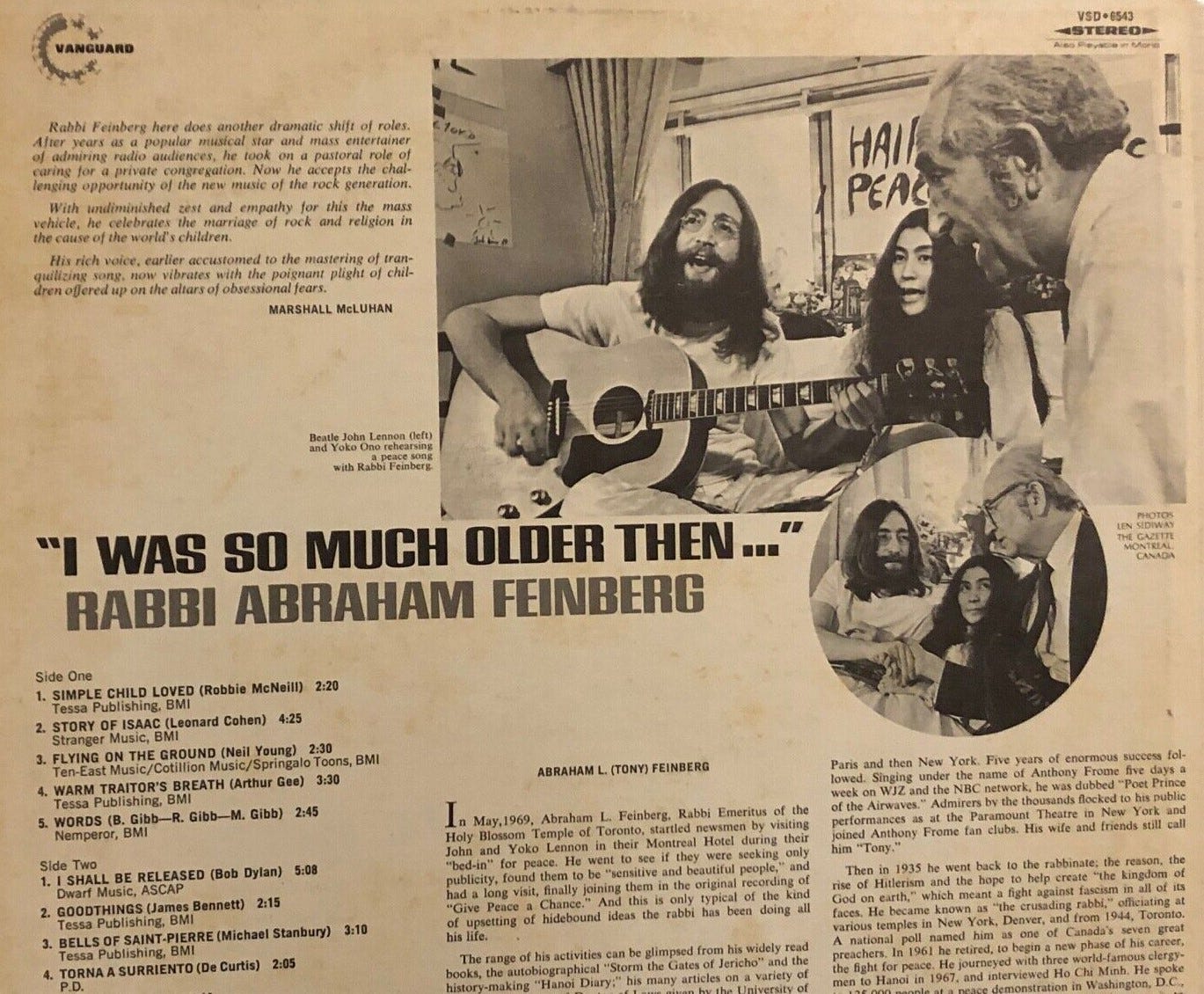

This resulted in an album. Rabbi Abraham Feinberg’s I Was So Much Older Then was recorded and released later in 1969. The title references Bob Dylan's "My Back Pages"; the song doesn't appear on the album—though the phrase perfectly captures its spirit—but Dylan's "I Shall Be Released" does, along with Leonard Cohen's "Story of Isaac," the Bee Gees' "Words," Neil Young's "Flying on the Ground," and the Neapolitan traditional song "Torna a Surriento" by Giambattista and Ernesto De Curtis. It was released on the Vanguard label in 1970 and produced by Brian Ahern and Athan Katsos.

The back cover features two photos of the rabbi with John and Yoko in Montreal, along with an explicit mention of the couple in his biographical profile and a quote from Marshall McLuhan. On the album, Feinberg lets his voice soar over songs with sumptuous arrangements, bringing the past together with the then-pop present, a combination that wouldn’t chart but resulted in an artifact that manages to capture another angle of an era of constant exploration and searching for meaning. It's a vindication of youth culture from a rabbi entering his seventh decade of life, who had done and seen it all.

Feinberg said to Lennon in that room in Montreal that he wanted "to serve God." Lennon replied, as expected, "It's the week to make God happy." And honor those words they did.

IV

Lennon and Ono’s campaign was quite successful on media terms. Feinberg did his part too. In 1972, the year John and Yoko released their most political album, Some Time in New York City (Apple Records), the rabbi returned to the United States, the place that, like the Lennons, he called home for the rest of his days. He worked in Berkeley, California; returned to radio, this time doing spoken activism; advocated for more dignified treatment of the elderly and for openness in discussing sexual issues with young people. He also continued writing and publishing books.

He didn't record more music, though: Tony Frome was a thing of the past, and the singing rabbi was a nice phase, but there were other things that needed to be done. Whenever he could, however, he remembered with joy the time he spent with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Because he sang, coherently, that we should give peace a chance. It never seemed like a bad idea to him. He knew what he was talking about.

Abraham Feinberg died in 1986 in Reno, Nevada. He survived John Lennon by almost six years. What he said after the Beatle's death we don’t know, but he surely said Kaddish for Lennon.

C/S.