When John Lennon arrived in California in October 1973, he carried a series of defeats on his shoulders. His creativity was in crisis after a universally misunderstood album—Some Time in New York City, released in June 1972—and another, recorded in haste and anxiety—Mind Games, released in October 1973—that did little to help his cause. While it was indeed an improvement, featuring brilliant moments, the public still struggled to trust the New York Lennon who had consciously distanced himself from the one who had charmed the post-Beatles world with Imagine.

John was at a critical juncture in both his personal and artistic life. Just a decade earlier, he had been at the pinnacle of the world with the Beatles and A Hard Day’s Night. In 1964, he visited the United States for the first time, staying at the Plaza—just minutes from the Dakota—and from there he conquered the world via television and radio.

By 1974, however, he was recovering from an intense period of political activism that had left him exhausted and disillusioned—though his idealism never entirely faded—managing his separation from Yoko Ono and learning to live in a world that had changed for him and everyone else. He was not alone, though: May Pang was by his side. His party-loving friends were around for many months. But Lennon, luckily, didn’t dive deeper into that lifestyle. We know how Keith Moon ended up. Even Ringo found himself, after years of chaos, in a hospital bed with part of his intestines removed.

John made it by acknowledging his talent. He focused on making music, teaming up with Harry Nilsson to produce Pussy Cats. As an album, it might be uneven, especially for two giants like them, but its value lies in the fact that it saved both their lives. Literally.

Pussy Cats marked a pause in the frenzy, a sharp turn on the road. Lennon could have been one of rock’n’roll’s casualties; instead, he emerged as one of its great survivors. Amid the chaos, he remembered—with considerable help from May Pang—that talent must be protected and nurtured. So, he stopped everything to be a musician once again.

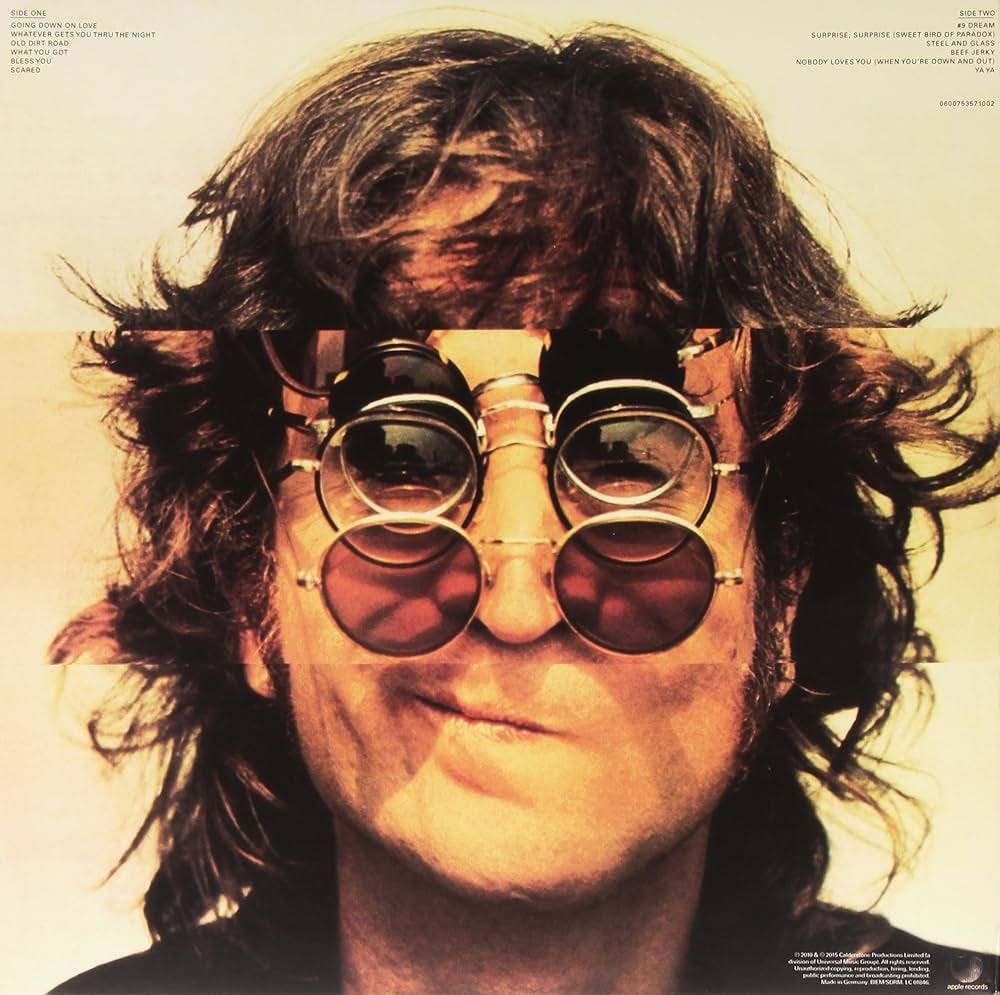

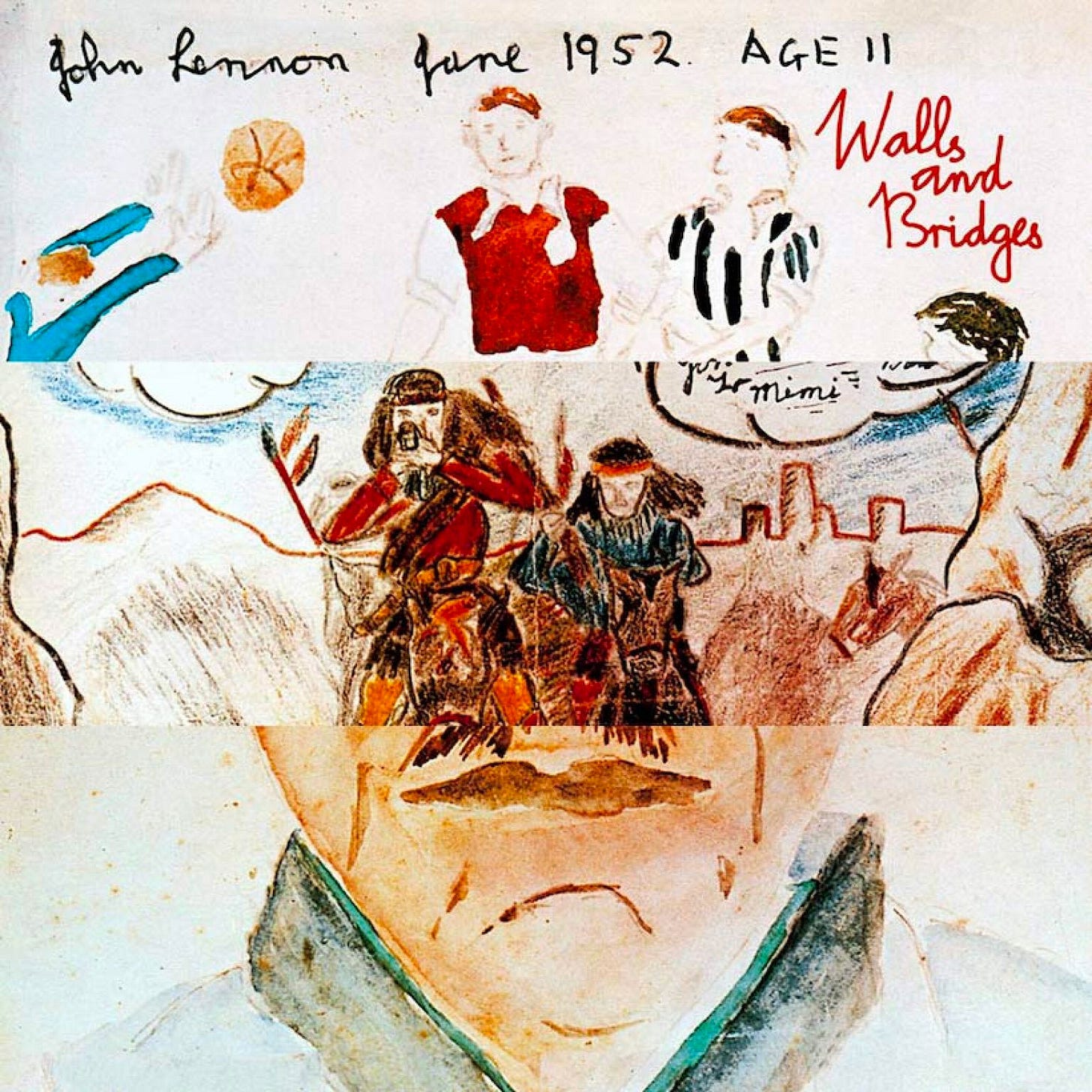

Walls and Bridges, recorded back in New York during the summer of 1974 and released on September 26 that year, serves as a refuge amid the turmoil, a spacee between two distant realities: the euphoria of success and the sorrow of emptiness. This is the album where Lennon truly embodies his identity, with little left to prove to the world. He was no longer the primal screamer of Plastic Ono Band nor the ex-Beatle looking for public validation of Imagine; he no longer felt the social pressure to write protest songs like those on Some Time in New York City and had moved past the uncertainty and creative block that plagued Mind Games from its inception. It is a collection of more balanced songs, ranging from a confessional diary exploring the psyche of a man who had it all—and thus had everything to lose—to someone who is delighted to be what he is despite—and as a result of—his many mistakes and missteps. Being a Beatle and reaching the peak of a career—perhaps a life—before turning 30 is both a blessing and a heavy curse known only to four people in history.

As in Mind Games, there is an uncomfortable longing for belonging. But like in Double Fantasy, Lennon asserts his need for solitude, domesticity, and a marks departure from playing pop star.

John Lennon referred to this period of his life as his Lost Weekend. But how much of it was truly a descent into darkness? It’s true he dove headfirst into the excesses offered by the sordid celebrity culture of Los Angeles, but it wasn’t a wild chapter like something out of Trainspotting. His antics were public and relatively few. While not downplaying them, they do not define the eighteen months he spent with Pang and, in a manner of speaking, apart from Yoko—they frequently called each other. It was a time of partying, but also of music, gatherings, and forward strides.

John rediscovered youthful love in May Pang; he opened the doors of fatherhood to his son Julian for the first time in eleven years; and he rekindled a relationship with Paul McCartney, which had broken down in 1969. Most of all, he reconnected with himself. It all started with a project to record rock’n’roll classics with Phil Spector, partly for legal reasons—settling a lawsuit with Morris Levy, who owned the rights to Chuck Berry's “You Can’t Catch Me” due to its similarity to “Come Together,” agreeing that Lennon would record an album of songs from the catalog to benefit Levy—and partly to return to his roots, something he had failed to do during the Get Back project. When things go awry, it's time to delve into biography. What had always given meaning to John’s life was rock’n’roll. It had to work. And it did.

But not in a straightforward way. The sessions with Spector were a disaster. There were heated arguments, threats, endless amounts of alcohol and even guns. If the legendary producer, creator of the Wall of Sound, could operate like that, Lennon couldn’t in the end. And, eventually, Spector disappeared with the recording tapes. Under different circumstances, Lennon might have collapsed. But this time, he had many things strengthening him. This time, there was May Pang. And a whole list of failures—relative, perhaps, since even the lowest point in John Lennon’s career is higher than many others—that had brought him to a point of no return, which made him even stronger. If anyone was going to get their way, it was him. Not even a notorious rogue like Spector would stop him.

Lennon connected with himself. Every time he achieved this, he had the rare ability to connect with the world. That’s what made him unique. That’s what made him John Lennon.

Walls and Bridges opens with “Going Down on Love,” which reveals a naked vulnerability and an uncontrollable lust from the very first breath. The sound is pure Lennon: a simple riff—related to “Well Well Well” from Plastic Ono Band—serving as the gravitational center of a song that flirts with euphoria but pulls back, lest it be consumed by desire. Love is both a refuge and a prison. Bridges, walls.

Lennon takes a walk on the wild side in “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night,” a hedonistic New York anthem that anticipates the spirit of Studio 54 that would open its doors a few years later. Yet it is also an admission of weakness and vulnerability: he will take whatever gets him through the night, be it metaphorical or literal. Nevertheless, it captures an euphoria he can no longer contain, a moment when Lennon lets his hair down. It is perhaps the moment when John most closely resembles, in his solo career, the confidence, swagger, and joy of his early days as a Beatle: he comes to accept himself, having arrived at a new version of himself where he feels at ease—and we know this won’t last, as he will eventually return to Yoko at the Dakota. Still, he is ready for a new kind of fatherhood, one he will embrace in a markedly different way from his first experience as a dad himself.

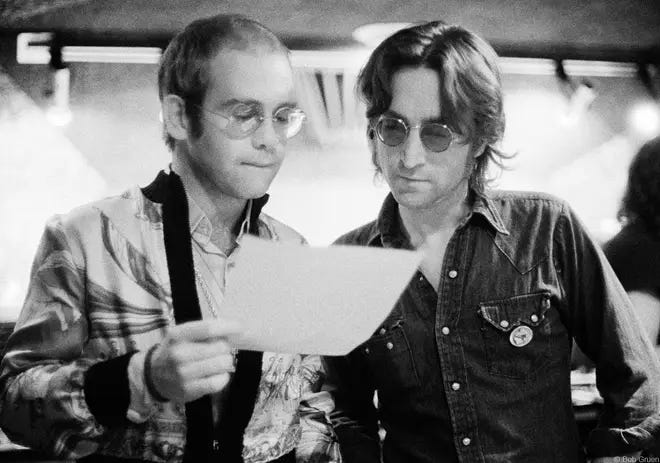

Elton John, collaborating with Lennon as an equal partner, elevates the song—based on a hit by George McCrae—with his drive and contributions, much like the other Beatles, especially Paul, did in the ’60s, a time that surely felt increasingly distant. It’s no coincidence that this became Lennon’s first solo number one on the Billboard Hot 100; it was to be his only one during his lifetime. This track could have defined the new phase of Lennon’s career had he continued recording in the following years. His open relationship with funk and black rhythms is evident here—though he always struggled with reggae, producing some peculiar but interesting moments, like “Do You Wanna Dance?” from Rock’n’Roll and “Borrowed Time” from the posthumous Milk and Honey. The same flair can be found in “What You Got,” which contrasts a bitter, resigned lyric with a cheeky, raucous sound, echoed in the instrumental “Beef Jerky.” They are all delightful in an awkward, charming way.

“Old Dirt Road” features a collaboration with Harry Nilsson, making me wonder what an album of duets between them might have sounded like under different circumstances than those of Pussy Cats. It’s an alchemical exercise blending two idiosyncratic styles, two distinct worlds, each with its own sounds and vibes. As often happens in such cases, the result lands somewhere in between. Yet that’s where its value lies: not in the explosiveness of a genius reunion, but in the compromises the two parts have to make to create something new.

In “Scared,” Lennon gazes into the abyss. Echoing Plastic Ono Band, this anxious song was written under the shadow of the fear of loss. It’s a raw anthem that may feel out of place for its time: it’s neither confessional in a Laurel Canyon sense nor explosive in the way of hard rock. Its theme is impossible to tackle amid glam, and punk has yet to emerge to transform its tortured message into something defiant, fuel for rebellion. Meanwhile, in “Steel and Glass,” Lennon returns to the bitterness of “How Do You Sleep?”—even featuring a similar arrangement—but this time, the venom is directed at Allen Klein, the manager he had trusted to take charge of his finances and career after Brian Epstein’s death and during the Beatles’ dissolution, only to be disappointed and ultimately betrayed by him.

The album closes on a tender note. While Plastic Ono Band concluded—with a touch of influence from the Beatles’ “Her Majesty”—with a fragment of dark, sordid mental rambling, a lament about his orphanhood (“My Mummy’s Dead”), Walls and Bridges ends with a celebration of life. “Ya Ya” is a snippet of what seems to be a longer session where John sings at the piano while his son Julian plays the drums. Originally sung by Lee Dorsey, this track was a nostalgic nod to the early rock’n’roll classics that had a resurgence in the ’70s—as films like American Graffiti by George Lucas demonstrated—and serves as both a vindication and a display of paternal love. The true father figure in Lennon’s life wasn’t the sailor who fathered him and disappeared to sea, only to return much later, but rather the music that made him feel connected to the world. Julian was born during Beatlemania, a time when Lennon was both distracted changing the world and terrified of fatherhood; while he never became a definitive figure in Julian’s life (perhaps only in his final and definitive absence), this brief aural moment is akin to a suburban father tossing a baseball to his child on a languid, sunny Saturday afternoon.

I first heard “Nobody Loves You (When You’re Down and Out)” in 1998 on the Wonsaponatime version. I was a child stepping into my early teenage years. I had saved money for weeks to buy the album, and after a disciplined first full listen, I immediately returned to this song. It struck me. I read the lyrics in the album booklet as one might read a biblical text in a yeshiva: trying to immerse myself in every word, sensing it had something important to tell me.

When I finally got Walls and Bridges on cassette at a flea market a few weeks later, I did so to hear the definitive version. It was then that I decided Lennon was my favorite artist for so openly expressing pain, a pain I had not felt yet but soon would; it was also the moment I resolved to dedicate myself, in some way, to music and words. I believed every word he sang, because “he’d been across to the other side” and was here to tell us all he had seen because he “had seen everything and had nothing to hide.”

At that time, I didn’t know he had written it with albums like Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning in mind—sonic tales about dark bars and sad men, scenarios that I didn’t know yet. Like the young narrator in Las batallas en el desierto by José Emilio Pacheco, who is surprised to be able, for the first time, to understand the very adult feelings that old boleros conveyed thanks to his first forbidden love, this song by Lennon ushered me, with conscious intent, into the next stage of my life.

If there’s one thing that can be attributed to John Lennon, it’s his deep sensitivity in turning his life into song. This doesn’t mean he couldn’t create from scratch; writing melodies was his craft, and he was always among the best at it. He had a knack for infusing even the most mundane aspects with meaning. He didn’t always succeed, of course, but that’s true for anyone, and it would be unfair to expect otherwise from him. Yet when he latched onto a melodic line, a verse, or a series of notes on his guitar, he made it his own. Then he would channel it through his voice and fingers, making it ours. His music is a gift, especially now, as his untimely death creates a chasm between his life and ours. It confronts us with the complex facets of our own nature: we must grapple with loss, vulnerability, and fear when Lennon felt them so deeply himself. He was one of us. Despite his wealth, his distance from the world, and his unusual life, he captured the essence of the shared human experience—whether poor or privileged, disadvantaged or fortunate: we all feel pain. It may differ for each of us, but no one escapes it.

Lennon sings with this understanding. “Scared”, for instance, is a genuinely real song.. If he fears loneliness, if he wades through uncertainty, then no one is unbreakable. It’s a rare comfort.

Black music is the cornerstone of John Lennon’s musical career. In the ’50s, it was Little Richard who reconfigured his heart and mind; in the ’60s, he reinvented himself through Motown and Stax; by the ’70s, he was wide open to the sounds of funk and the emerging disco scene. Additionally, he lived in New York, the capital of the world, where the emotional amalgams of Black culture, Latino, Irish, Jewish, and Italian influences create a zero point of relentless creativity. It’s a vibrant city shaped by its diverse parts.

This suited Lennon well. Smokey Robinson and George McCrae spoke directly to him. If, according to the official narrative, he transformed into a pop Caligula in Los Angeles, he regained focus and purpose upon returning, hand in hand with May Pang, to a tumultuous New York. They took refuge at the Pierre Hotel, where, although the excesses continued—some of which became famously publicized later, involving David Bowie—creativity also resurfaced. His two previous albums were a generic exercise in protest music—Some Time in New York City, which I still consider an unrecognized influence on the future punk scene that sprouted around CBGBs, but that’s a whole other topic—and an attempt to reignite his creative candles through the summoning of old spirits—Mind Games and its magnificent title track that shines within a desperate album. But in 1974, Lennon encountered a new version of himself. He decided he had abused his freedom enough and focused on redirecting it toward creation. Like an epic hero from classic literature, he found strength in darkness and managed to generate light.

In Walls and Bridges, John Lennon sings, plays guitars and piano, and produces. Jesse Ed Davis plays lead guitar, we have Klaus Voorman on bass, and Jim Keltner on drums. Ken Ascher handles keyboards, while Nicky Hopkins plays piano. Bobby Keys shines on tenor saxophone (accompanied by Ron Aprea, Frank Vicari, Howard Johnson, and Steve Madaio), and Arthur Jenkins plays percussion, with Eddie Motau strumming acoustic guitar. The Philharmonic Orchestra, led by Ken Ascher, provides strings and brass arrangements. Joey Dambra, Lori Burton, and May Pang sing the beautiful chorus of “No. 9 Dream.”

Lennon in 1974 is more centered and aware of his place in the world. While still grappling with his demons, he also opens up to new possibilities. This album is not just a reflection of his emotional state at the time; it’s a bridge to his future. It’s an album of reconciliation: mostly with himself.

Understanding it this way, Walls and Bridges becomes more than just an album. It’s a work of an artist in transformation; if in Plastic Ono Band Lennon confronted his demons, in Walls and Bridges he takes them out for a stroll, invites them for Brandy Alexanders, and dances with them through the streets of Hell’s Kitchen.

“Surprise, Surprise (Sweet Bird of Paradox)”, dedicated to May Pang, is one of the sweetest love songs of Lennon’s solo career, yet it doesn’t reflect the frank and candid Lennon we’re accustomed to hearing in his ballads. This love is of a different kind and nature—perhaps reminiscent of what he experienced with Cynthia Powell in that distant Liverpool of the early ’60s? (In fact, Pang and Cynthia got along very well.)

One could say May Pang is the most significant influence on this album. Their relationship, which developed following his separation from Yoko Ono and under the latter’s direct influence, was profound. Although not without the turbulence characteristic of Lennon, it was marked by tenderness, acceptance, and openness, according to Pang’s many testimonies: two books—Loving John (1983) and Instamatic Karma (2008)—numerous interviews, appearances at conferences and festivals, and a definitive documentary—The Lost Weekend: A Love Story (2022), directed by Eve Brandstein, Richard Kaufman, and Stuart Samuels—that tells a story that cannot be silenced anymore.

Lennon always needed a collaborator. Pang was that for him. She restored his confidence and optimism, his carefree spirit and creativity.

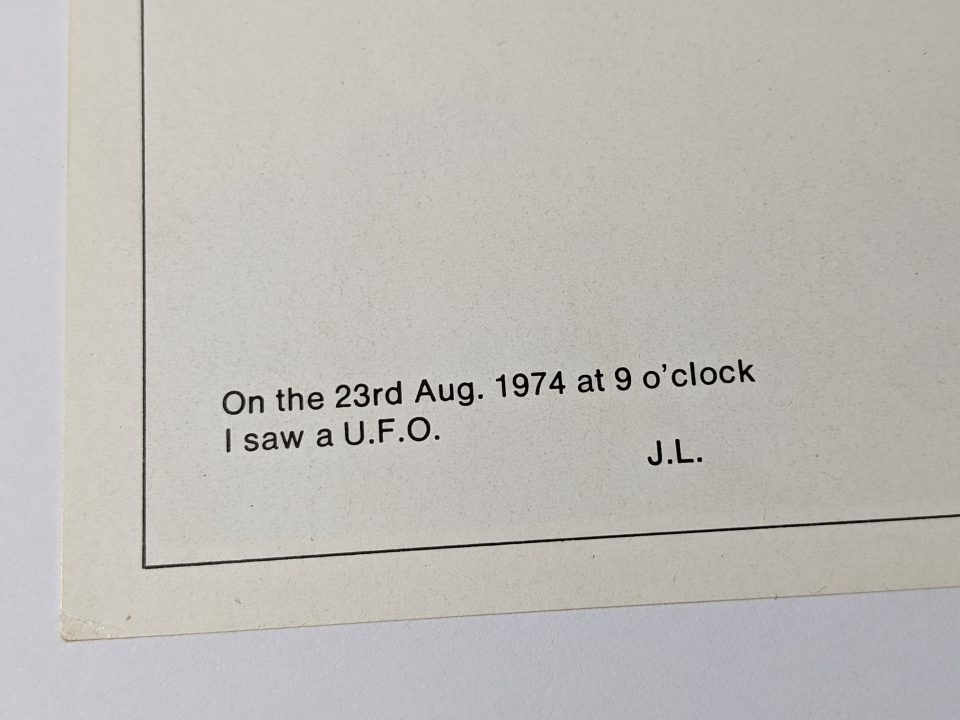

Their relationship is poetically illustrated by an episode involving a UFO sighting on August 23, 1974, from the rooftop of their New York apartment at 434 East 52nd Street. This event is noted on the inner sleeve of Walls and Bridges (and, indirectly, in the lyrics of the posthumous track “Nobody Told Me”).

Lennon and Pang were together when they spotted a bright light in the sky. According to Lennon’s account, the light seemed to move strangely, transforming from a simple flash into a floating object that changed colors. Intrigued and excited by the experience, Lennon described how the object appeared to be more than just a star or an airplane.

The sighting not only captured Lennon’s attention but also prompted him to reflect on new meanings of life and existence, pondering other possible worlds. In several subsequent interviews, he expressed his fascination with the topic, considering the possibility that we might not be alone in the universe. This incident also mirrored the cultural atmosphere of a decade marked by unrestrained creativity, yet riddled with loneliness, disillusionment, and the loss of the ideals of love, peace, and creativity that had characterized the previous decade.

It’s unnecessary to question the reality of the UFO sighting. It serves as a symptom of the freedom Lennon found in his closeness to Pang—a flicker of trust in a hostile environment in every sense. Because May was not just a muse or an instigator, but a partner. Their relationship was not without complications: Pang has described her bond with Lennon as filled with moments of joy, but also insecurities. Yet, on that rooftop overlooking the East River, something unexpected, surprising, and hard to believe occurred. The unknown manifested. Pang offered Lennon a space—both corporeal and spiritual—to explore aspects of his personality and artistry that had been suppressed or hidden. The sighting was, then, a moment of revelation, an epiphany, a complicity: only they witnessed it. It became their private joke, a little mystery shared by two hearts only, their open secret. A manifestation of an improbable love that partly died on December 8, 1980, and will leave the world the day May Pang departs—may she live to 120—but will forever be captured in song. And testified to by an unidentified flying object in the Manhattan sky that arrived, stayed for a moment, and vanished.

In the autumn of 1974, both George Harrison and Ringo Starr released albums. Each, alongside Walls and Bridges, can be seen as reflections of the vital moments in each of the ex-Beatles’ lives.

In contrast to John, Harrison released Dark Horse, perhaps his darkest album. Far from the frankness and combativeness of Plastic Ono Band, it reflects a struggle against expectations and success through spirituality and nostalgia. The guitarist’s dissatisfaction, now distanced from Lennon despite their past collaborations after the Beatles’ split, manifested in his voice. While Harrison often provided mystical interpretations of the world, it’s hard to accept the story of laryngitis. That may have been the medical explanation, but his negative feelings formed a knot that stifled his expression.

Ringo Starr, on the other hand, released a relaxed, accessible album. Goodnight Vienna—named after a song written by Lennon—sought to be a sequel to his previous mega-seller, Ringo. With a touch of glam and a hint of old rock ’n’ roll, along with some mischief and contributions from John—who composed the title track and arranged a bold version of “Only You” by The Platters, along with help from Harry Nilsson and Richard Perry—this marked Ringo’s last big laugh for a long time, his final major success, and the closing chapter of his own streak of fame as a singer, actor, and party animal that had lasted for several years.

Paul McCartney tells a different story, as usual. In December 1973, he released Band on the Run, an album that nearly killed him—recorded in Lagos, Nigeria, he was robbed at knifepoint; also, the humidity and climate took such a toll that he thought he was having a heart attack. Yet this masterpiece catapulted him to the newfound status of pop royalty of the ’70s—not a small feat—and remains difficult to surpass even today. He was the only ex-Beatle to form a new band, Wings, and it seemed to work for him; much like with Sgt. Pepper, Paul found a transformative mechanism to become someone else in order to reach his most authentic self.

The polished, cohesive, joyful, and energetic sound of Band on the Run stood in stark contrast to Lennon’s albums up to that point. Where Lennon was rootsy and tortured, McCartney was onomatopoeic and upbeat. This isn’t to say McCartney lacked depth—he has a way to transform any uttearance into something of substance—but his approach to music differed. Without Lennon, he appeared more naive, drifting toward a blinding light. Conversely, without McCartney, John seemed more taciturn, veering toward a ravenous darkness.

In Band on the Run, the tensions created by the breakup—compounded by Allen Klein and various misunderstandings—began to soften. Despite the barbs in songs like “Too Many People” and “How Do You Sleep,” both artists managed to dodge the venom in the end. McCartney even crafted the most Lennon-esque song of his repertoire, “Let Me Roll It,” to which Lennon responded—consciously or unconsciously mirroring the riff—with the guitars in “Beef Jerky” on Walls and Bridges. Indeed, bridges were being built.

Walls and Bridges also manifests Lennon’s artistry, offering glimpses of the genius he displayed in his mid-’60s books—In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works—and in his sporadic ventures into the visual realm, like his short films with Yoko Ono, his drawings and lithographs, and his wordplay that blended the Goons with Lewis Carroll, peaking in “I Am the Walrus.” The cover art features panels with his childlike drawings, hinting at the genius that observes and reinterprets. He initially intended to use these for the Spector rock ’n’ roll album, but when that project fell through, he decided to incorporate the design anyway to his new creation. Thus, Walls and Bridges stands as his most personal album—a manifesto that isn’t as contrived as “Imagine” or as longing as “(Just Like) Starting Over.” It’s Lennon in his own write.

“Bless You” and “No. 9 Dream” are two of Lennon’s most beautiful songs.

The former distills his melancholy and resignation to loss: it’s the complete opposite of his primal scream era—“Cold Turkey,” “Mother”—but also contrasts with his songs about insecurity and uneasiness like “Jealous Guy” and “How?” It also represents a different point of maturity compared to his Dakota-era songs like “Woman.” Here, Lennon is freer and purer, accepting defeat, heartbreak, and disillusionment: he embraces his humanhood—albeit one more famous than Jesus Christ—and, far from the plaintive tone of “I’m A Loser,” the desperation of “Help!” or “I’m So Tired,” the suicidal edge of “Yer Blues,” the bewilderment of “Isolation,” or the defeat found in “God,” he emerges as someone who has learned to forgive (especially himself) and feels ready for whatever comes next without holding onto unnecessary grudges, not even as fodder for artistic creation.

“No. 9 Dream” is pure Lennon. Dreamlike, surreal, psychedelic. But not in an academic sense, as if he were a craftsman invoking minor demons; rather, as a thaumaturge constructing a world from his deep connection to it. John felt a kinship with the number 9, which, beyond its appearances in his life—like his birth date or the numbers of his residences—carries meanings in numerology that Lennon might have intuited, like in the Hebrew yesod (יסוד), the ninth sefirah of the Kabbalah associated with the moon, the sexual organs, and the connection to the earth, nearly completing a cycle, victory, rebirth, hope.

Yet without delving into esotericism, “No. 9 Dream” approaches sonic perfection. If Lennon created sonic miracles in the ’60s like “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “A Day in the Life,” the central song of Walls and Bridges plays in that same league. It’s a splendid display of imagination and inventiveness, a track that inhabits a sonic and emotional territory that “Across the Universe” aimed for but fell short of amid the production and management conflicts of those years. “No. 9 Dream” embodies the sound of dreams, like Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory translated into music—a liminal sonic space between the universe that borders the territory between Freud and Elvis, and the potential future of what pop music could—will?— become.

All of this unfolds in Walls and Bridges, which ultimately is just a simple pop album pressed into black plastic, with 46 minutes of music on two sides. An artifact like so many others that were part of the market of an era, yet primarily a reflection of a collective consciousness that peaked in that year and then faded. From then on, politics took precedence as a position of hatred against the other, violence became a lazy means to secure the resources produced by industry for survival, and cynicism turned into a survival tool. Lennon told us the dream ended in 1970. But he awakened before anyone else, as the visionary he was. The closure of the 20th century began precisely during these years and reached a definitive point in a New York where Lennon no longer walked, a victim of the violence that would eventually catch up to all of us, on a sunny Tuesday in September 2001.

We have to duty to keep on writing this cadavre exquis we call history. Lennon wrote a whole chapter for us. It is now our duty to write an entirely new one that finally conquers his ideals of peace and love. We have The Music—his music. More than a weapon, a tool, because it constructs more than in destroys.

And, anyway, whatever gets us through our lives is alright. ‘Salright.

C/S.

What a wonderful article. Walls And Bridges is my hands-down favorite Lennon album. It’s as personal as his Plastic Ono Band album, but without the desperation. There’s a hopeful quality to the songs, even as he peers into the dark places of the soul. It’s the work of a matured artist.

#9 Dream is like a Dali painting- such a good analogy. It’s the loveliest thing he wrote, post-Beatles. I always want the song to go on longer (I always have to play the song at least twice when I hear it, it’s like a little world unto itself, only rivaled by Strawberry Fields I think…).

Anyway, thanks again! What a wonderful gift for what would’ve been my first musical hero’s 84th Birthday.

OUTSTANDING. Now THIS is how to write an overview of an album. Very astute readings of the songs and "Bless You" for recognizing May Pang's influence.

One minor detail though, and it's just my interpretation though I think I saw it somewhere else, "Going Down on Love" can also be seen as a song about submission to love, about the give and take and compromises relationships demand. "Going down" is a crude metaphor based on a sexual term but it does fit the message I thought he was trying to get across.

You're now two cents richer. Thanks for this, it has made my morning,