Don’t Forget Me: 50 Years of 'Pussy Cats' by Harry Nilsson (and John Lennon): A Critical Reevaluation

Harry Nilsson has a song, his voice breaks at 2:05

Something about the way he says, «Don’t forget me»

Makes me feel like

I just wish I had a friend like him, someone to get me by

Lennon in my back, whispering in my ear, «Come on, baby, you can drive»

—Lana Del Rey, “Did You Know that There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd”

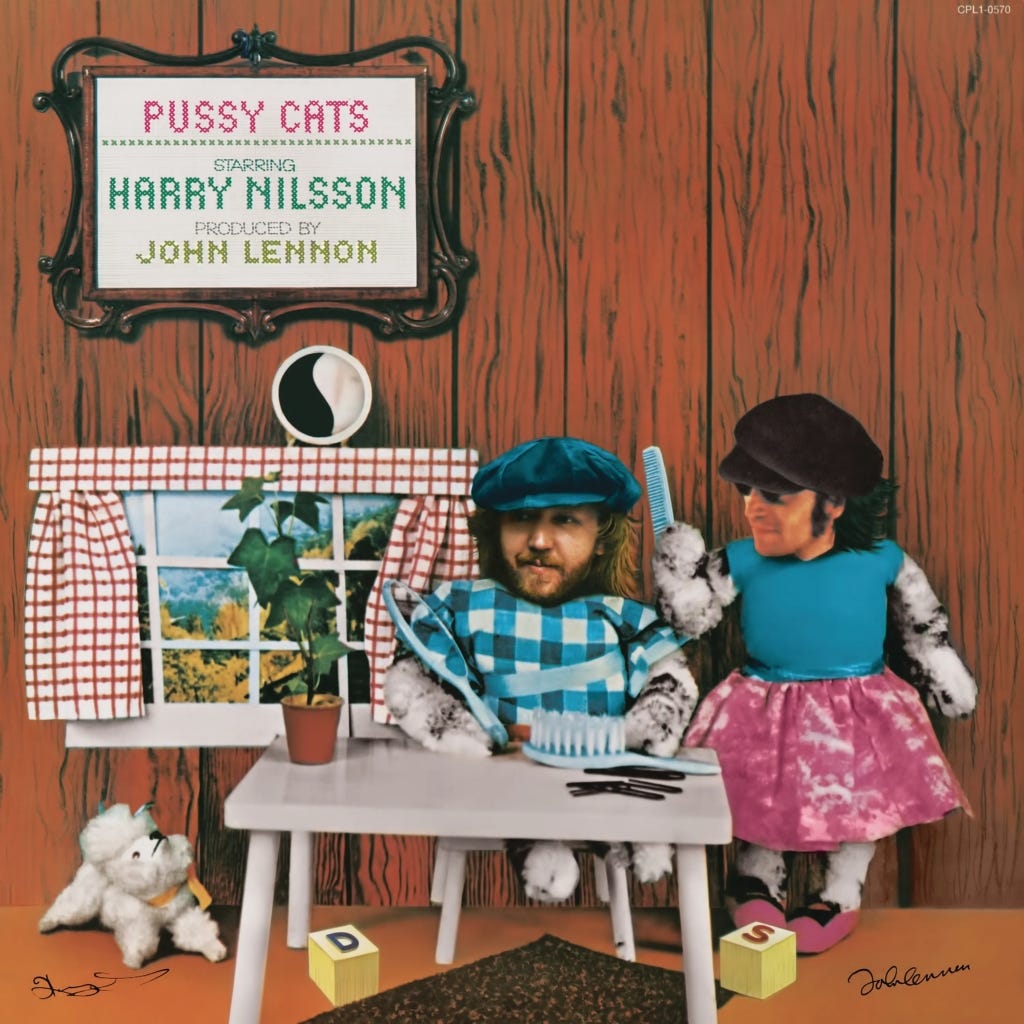

Fifty years—what does that mean? On August 19, 1974, Pussy Cats, Harry Nilsson’s tenth studio album, was released for the first time. Produced by John Lennon during his “Lost Weekend” in Los Angeles, California, the album is often viewed as a reflection of the volatile creative lives of its two creators but, today, it seems to be merely a footnote in the careers of both Nilsson and Lennon.

However, Pussy Cats deserves more than that. It is an album that requires a fresh perspective and a clear mind to truly appreciate what it is: an anti-masterpiece of sorts from which much can be learned in an era dominated by computer-generated songs, corporate playlists, and the relentless demand for brevity, conciseness, and sterile perfection in sound and creativity.

★

Nilsson is one of pop’s most enigmatic geniuses, a marginal figure who nonetheless had a profound and multifaceted impact from the start. Born in Brooklyn in 1941, he had a troubled childhood (as his songs "1941" and "Daddy’s Song" recount) and, once old enough, headed to Los Angeles, where he took on various menial jobs that eventually led him to a desk job at a bank. In the U.S., this was the era when institutions were just beginning to use computers. Harry had a peculiar knack for these machines and ended up being an indispensable employee. However, there was a quiet musical affinity in his family that, when it came to him as a blood inheritance, became a vital pulse.

He was a prodigious songwriter and a magnanimous singer. One of those rare talents that come around only occasionally, pursued by incessant demons throughout his life; one of those individuals who stand under the spotlight to remind us of how beautifully hard and complicated it is to be human.

Nilsson never sought to be a rock star through conventional means: it’s hard to imagine his biopic directed by James Mangold, for instance. In an era when musicians strived to project an image of grandeur and exoticism, he saw himself as a pop worker, a ghost in the machine. Inspired by the great American composers of yesteryear—George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin—he viewed himself as a songsmith and, to be one, had to dedicate himself entirely to the realm of tunes. Everything else—the public image, the extroverted personality of the artist—was an add-on to bring the songs to the audience, part of the pop commerce, but not its core.

He was always a furiously experimental artist, only not in the static sense often associated with the term: Nilsson crossed genres and experimented with different ways to approach that entity called the song, but most importantly, he created bridges between seemingly disparate worlds. He studied the Beatles with a sharp eye, listened to Phil Spector with a clinical ear, and was astonished by 20th-century music, which boasted itself a vast array of influences, styles, and proposals. Free from prejudices, it was as natural for him to listen to—and later sing and compose—wild rock 'n' roll and Broadway musical tunes; he saw no difference between the lovesick yearning of Motown soul and the humorous antics of music hall. To Nilsson, they were different facets of the same thing: human expressiveness.

It’s fortunate that Nilsson existed in the years following Spector, the Beatles, and Pet Sounds, because he made the recording studio his natural habitat—he gave few concerts and never went on tour—and his playground. He approached the space as if it were an additional collaborator, the 11th player on his team; he used it to create sound and texture from vibrations and distances. He also knew his own physical and vocal abilities to shift from melancholy to sarcastic with just a inflection, and he made the most of it: his songs contain a vast emotional range, and it wasn’t necessary to understand the words because he knew how to sing feelings with a stunning ease.

Still, Nilsson is the master of the anti-hit. Not because he didn’t have hits—he did, and they are gargantuan—how can one not mention "Without You" by Pete Ham and Tom Evans of Badfinger, perhaps the most tragic number 1 in pop history; or "Everybody’s Talkin’," "Without Her," "One," "Daddy’s Song," all of which charted when performed by others—but because what mattered to him was that the song existed and had a life of its own. No one sang them like he did, especially his own compositions—and here’s the irony that some of his biggest hits as a singer were written by others—but his ironic and detached approach to fame and success, his rejection of self-satisfaction, and his creative drive place him in a very particular—and solitary—league in the canon. It’s hard to imagine a pop enthusiast with a Nilsson poster above their bed or a shirt with his face under a parka or leather jacket. Nilsson is not as mainstream—though he should be—but his voice has had a long reach. Play “Without You” for any passerby, and you’ll captivate them.

Nilsson had a rare talent—like that of great soul singers, like that of major poets—for creating moments of deep intimacy with his music. Often, his songs are, despite his enormous voice, conversations in whispers rather than grandiose statements. When the pop music of the '60s and '70s embraced complexity and extravagance, Harry was the genuine embodiment of simplicity. Nilsson is, in some way, a refuge from life’s senseless noise and vertigo.

★

John Lennon referred to the 18 months between the fall of 1973 and the spring of 1975 as his “Lost Weekend,” a time during which, for various reasons, he was separated from Yoko Ono. During this period, his assistant, May Pang, became his partner—in every sense of the word—through an extended stay in Los Angeles, a return to New York, and a series of public escapades that were well-documented by the press, making this time seem like a mere interlude in the life and career of one of the defining musicians of the 20th century. However, with the benefit of time and perspective, we now understand that the "Lost Weekend"—a term borrowed from Charles R. Jackson's 1944 book later adapted into a film by Billy Wilder, which depicts an alcoholic writer lost in the haze of his addiction—was not as lost as it seemed. In fact, Lennon only called it that way retrospectively, once reunited with Yoko and from the standpoint of a settled domestic life with new responsibilities and circumstances.

These months were marked by intensity and reconnections. Lennon reunited with old friends—Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, Micky Dolenz, Mal Evans, Klaus Voormann, and even his son Julian—and met the new generation—Alice Cooper, Marc Bolan, Keith Emerson, John Belushi—returning to a life of excess, trial, and error reminiscent of his teenage years. One might argue that his time and tours with the Beatles had already offered opportunities for indulgence, but the constraints of being one of the four most famous people in the world were immense. Moreover, separating from Yoko and being with May Pang, his assistant and lover, his confidant and friend, was part of a relationship that, despite the scandals, moderated his ever-volatile tendencies toward grandiosity and self-loathing. She was his girlfriend, his guide, and his mirror: while it has always been argued that Yoko Ono orchestrated the separation to maintain control even when they were apart, the Lennon-Pang affair was genuine and loving. John had a tragically short life, but it was longer than it might have been thanks to May Pang.

★

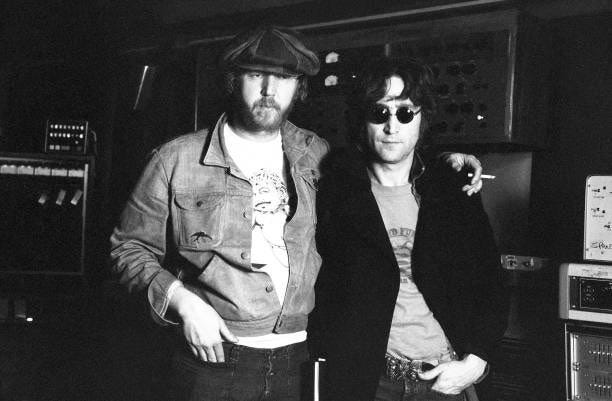

Nilsson. Lennon. Two characters in search of an author. Two titans caught in a whirlwind of excess and liberation, craving rupture while also yearning for a return. Two rebellious souls breaking things in the hope of finding love amidst the scolding, perhaps.

It was a time of chaos and creation.

★

At the heart of Pussy Cats, beyond the excesses and recklessness, lies a raw and disheveled sound that contrasts sharply with Nilsson's usual sophistication. This is partly due to the influence of a disillusioned Lennon searching for the Next Big Thing, who senses that rock 'n' roll might save him again as it did in his Liverpool youth years. It’s not just the waiting for a messiah with a pompadour and swinging hips: it’s about making it possible with a 4/4 beat, the usual three chords, a touch of boogie and twist, and some shouting. There’s no time for embellishments; the focus is on capturing the effervescence and turbulence that surrounded them. Pussy Cats has many faults and can be rightly criticized, but never for failing to be an honest album.

Nilsson also places his faith in rock 'n' roll. But he does so not with a revivalist zeal like Sha-Na-Na. Under Lennon’s guidance, he draws from the 1950s suburbs the awe of encountering alien and urban music: “Save the Last Dance for Me,” a song written by two Jewish men—Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman—produced by two other Jewish men—Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller—and performed by four African Americans, the Drifters, led by Ben E. King, a hero to Lennon, is a prime example that the American Dream was in its cultural crossroads, and its crystallization terrified those who, in fact, held the power. There's also Bill Haley & His Comets' “Rock Around the Clock,” the song that transformed the world, the mainstream mediation of Black sound, the channeling of the instinct for change that is, ultimately, the instinct for survival.

We also find “Loop de Loop,” a song by Johnny Thunder, a Florida church singer who, along with the Bobettes—a choir from East Harlem—was instrumental in the secularization of gospel, that sin which, in reality, was more of a virtue because it united consciousness and reminded us that race is a political, imperial, and colonial construct that should be discarded as it is an obstacle to dialogue. And of course, Nilsson and Lennon chose to open the album with Jimmy Cliff’s “Many Rivers to Cross,” the legendary Jamaican, a reluctant subject of the crown to which Lennon returned his MBE under superficial pretenses but with perhaps unfathomable reasons—a song of pain and discontent, uncertainty and wandering, exodus and prayer. Lennon was so proud of his string arrangement that it served as the foundation for his “No. 9 Dream” a few months later.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” by Bob Dylan is an anthem to the distance of otherness, a chronicle of industrial societies that, despite the revolutions they’ve undergone, return to their dismal patterns of exploitation and dehumanization. And, moreover, it’s a fun, bouncy song, a primitive rap that, if we get super-Talmudic about it, could be considered a poem that, thanks to a series of fortunate accidents, might become part of the liturgy of the post-urban (sub)world. Nilsson’s version moves away from Dylan’s cynical lament and brings it into the realm of glam rock Bolan-esque, hedonistic, bodily, drug-fueled territory. The world is here and now.

In the original songs, Nilsson, along with Lennon, explores his own descent, shrouded in a cloak of despair that echoes the Spectorian production of the ex-Beatle. His voice, rougher and more wounded than ever, a marriage of the velvet of A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night and the razor of Plastic Ono Band, sings with a vulnerability that resonates with the intensity of the moment. If there is an album that sounds like 1974, this one is a huge contender.

“All My Life” is a raw song wrapped in strings and winds; after all, we shouldn’t ruin the universal party. There, amidst the tumult, one can always find a kindred spirit to guide or at least accompany us on this winding path that guarantees nothing: if Lennon and Nilsson, who seemed to have it all, were lost, what can we expect of ourselves? There is no ideal human, and Lennon told us this in “God,” just as philosophers, sages, and Talmudists did in the past.

“Old Forgotten Soldier” is the sister song to his acclaimed “1941,” but here Nilsson is truly a survivor of his own war: it’s a song where his voice breaks, not out of emotion, but because it was stretched beyond its limit. During the sessions, Harry literally lost his voice; his vocal cords gave out from excesses, pain, and the demand of singing. In this track, he is occasionally off-key, noticeably out of shape, gasping for air, unable to paint the notes no matter how much he waves his brush. Some people close to him say he never fully recovered, that this moment in 1974 marked the final chapter of his life, which ended twenty years later: like a football player, Nilsson made an effort to reach a ball that was slipping away and broke a part of himself in the process. Though he played many more games afterward, he never did so with the agility of his earlier years.

In “Black Sails,” Nilsson takes the helm of a ship in a sea he seems to command, that of orchestral ballads, but here he is out of control and sounds like a pirate adrift. A lover who sees everything ending once again, knowing he must let go because it's the only way to survive, and life may be the most precious thing, even above love. Dawn may bring a new shore, hopefully, but if not, the journey has been enough because, if not, what is life really? “Mucho Mungo/Mt. Elga,” co-written with Lennon, is like this character touching land, happy to feel the sand beneath his feet but still lost: no matter how high he climbs, he finds nothing but more walls. It’s enough to be alive, but why does it have to be so difficult?

“Don’t Forget Me” may be the central song of the album, a display of emotion and sincerity. Both the lyrics and music convey a vulnerable plea: the fear of passing through life unnoticed, of living without truly living, of being in the world without leaving a mark when one is gone.

★

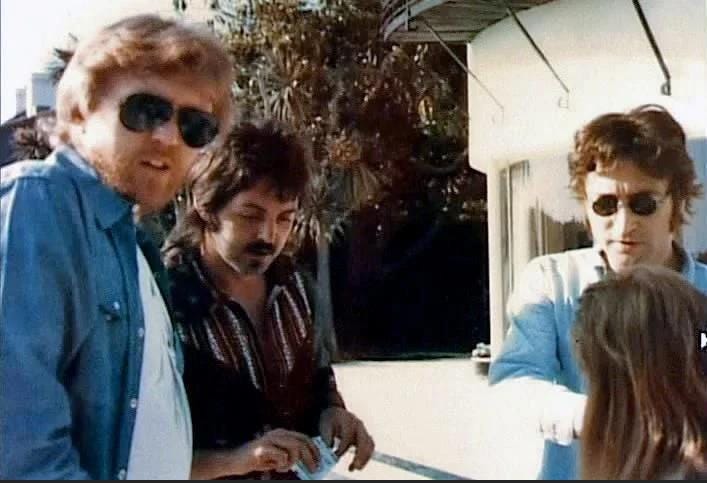

The first session for Pussy Cats took place on March 28, 1974, at Burbank Studios in Los Angeles. That night, Paul and Linda McCartney showed up. Among the attendees, more in party mode than working, were Stevie Wonder, Bobby Keys, Jesse Ed Davis, Ed Freeman, and friends Mal Evans and May Pang. Lennon welcomed the other Beatle and his wife with magnanimity. Macca took a seat at the drums while Linda played the organ. They jammed for a while, accompanied by Wonder on electric piano, Keys on saxophone, Nilsson at the microphone, Davis on guitar, and Freeman on bass. Pang played the tambourine. The session was largely unproductive—most, if not all, were under the influence of strong Californian drugs at that hour—but it is the last recorded instance of Lennon and McCartney playing together in a studio. Parts of the recordings can be heard on a famously unpolished bootleg, A Toot and a Snore in ’74.

In the following days, Lennon and McCartney rekindled their friendship. Although they saw each other many times in the years that followed, the last known photograph of them together was taken by May Pang during these days.

★

It’s important to acknowledge that Pussy Cats is not an easy album to digest. It is uneven, dark, disconcerting. Brutally honest, often at the listener's expense. But therein lies its secret: it is a collection of songs written and recorded in an ethereal environment influenced by alcohol and drugs, a new and uncomfortable freedom—akin to what one might experience from a divorce, the death of a loved one, or release from incarceration—a quest for personal redemption in a permissive setting.

Fifty years later, it remains one of those works that may never be part of a canon (like those ever present and often contrived best of lists), but serves as a counterpoint to it. Pussy Cats reflects the complex relationship between creation and personal life, between the search and the discovery; it is one of those works that reminds us that creativity involves attempting and abandoning, otherwise no finished product emerges. Pussy Cats is a snapshot of a moment in the lives of Nilsson and Lennon, of the 1960s pop aristocracy, which, a decade after its peak, faces the possibility of decline, much like any historical patriciate. However, it is also a portrait of friendship and companionship: even amidst chaos, it’s possible to shine brightly when one has a partner who resonates in harmony.

★

The allure of failure, especially when it comes from iconic figures like John Lennon and Harry Nilsson, can be captivating. The—relative—failure of successful individuals is intriguing because it reveals a vulnerable side that brings us closer to our heroes, who may seem unattainable. Lennon and Nilsson were never perfect, even though they reached unimaginably high creative peaks on many occasions.

In cultural narratives, failure often precedes overcoming adversity and eventual success. Stories of established figures who face difficulties and make mistakes are especially appealing because they reflect the possibility of redemption. Or because they provide comfort to those who remain static and offer a rationale for their own stagnation.

However, failure is an intrinsic part of the creative process. This is not to say that Pussy Cats is a failure—I’ve tried to prove quite the opposite—but it is an album that functions in the popular imagination as an anomalous and misplaced work, swallowed up by the mythology of Lennon’s "Lost Weekend" excesses and Nilsson's affected voice. This stigma calls to be lifted. It is not the masterpiece of either artist, but it didn’t have to be. Instead, it stands as a testament to creativity and perseverance, a demonstration that art can be transformative without being complete: it was a springboard for both to take different paths in their careers after a period of hedonism and decline. On one hand, it provided a sense of possibility and novelty because Lennon and Nilsson partied like teenagers—so much talk about the inner child and so little tolerance when it truly appears—and, at the same time, they anguished like old men because they carried the experience of turning creation into a craft and a journey.

In many cultures and mythologies, the fallen hero is a powerful archetype because it reflects the depth of the human experience. But perfection is not a prerequisite for greatness or relevance. Exploring the depths of our condition perhaps is. In that sense, Pussy Cats serves as an illustration.

★

Among Harry Nilsson's essential albums, Nilsson Schmilsson (1973) is a standout, showcasing both the bittersweetness of "Without You" and the whimsical lightness of "Coconut." Also indispensable are Aerial Ballet (1968) with tracks like "One," "Daddy’s Song," "Good Old Desk," and "Everybody’s Talkin’" (written by Fred Neil and featured in the Oscar-winning film Midnight Cowboy), Pandemonium Shadow Show (1967) with the timeless "Without Her"; Harry (1969), including the gorgeous "I Guess the Lord Must Be in New York City," and the incredibly smooth A Touch of Schmilsson in the Night (1973) with its flawless reimagining of the American songbook. Not to be overlooked are Nilsson Sings Newman (1970), where he covers the songs of American composer Randy Newman, and the eccentric Son of Schmilsson (1972) with "Spaceman" and Richard Perry's heavy production.

However, on reevaluation, Pussy Cats truly deserves to be in this company. It stands as an ode to creative chaos in which most things landed on its feet. It reflects a period of upheaval, personal and professional turmoil, altered states of mind, though far removed from the days of yellow submarines and skies with diamonds. The frenetic nightlife of Los Angeles produced an imperfect, disorganized, and unorthodox album. Lennon, from his position in the control room, attempts to channel Phil Spector but falls short; Nilsson strives to remain himself but doesn't quite succeed. Instead, improvisation and spontaneity prevail.

The album was recorded in an informal and relaxed environment. Rather than a polished and meticulous production, Pussy Cats captures a raw and direct quality. There was little planning and a lot of commitment to the moment. It’s an album about living and feeling the present, with its rough, emotional, and disillusioned tone, reflecting the unfulfilled promises of fame, from two survivors of the Greatest Decade Known to Man trying to find meaning in the old rock’n’roll that gave them so much—and to which they gave so much in return. The reinvention occurred. Nilsson made his most grim and streetwise album. A few months later, following the pattern of Pussy Cats, Lennon recorded Walls and Bridges, which yielded him his only number one single in the US of A.

Pussy Cats delves, at its core, into internal struggles, discontent, and the possibility of personal redemption. Chaos and improvisation are tools used to capture on tape a small, imperfect artistic manifesto.

Fifty years later, there may be a valuable lesson here for a contemporary musical environment dominated by digital production, artifice, and viral trends. Authenticity remains valuable, creative experimentation is worthwhile, genuine collaboration matters, and music can be personal without being introverted or sly.

In an age where music is shaped by algorithms, Pussy Cats can remind us, if we listen closely, of the importance of emotional depth, imperfect music, broken voices, and lives spent in creation. Today, as value is measured in numbers, transcendence is once again questioning its true nature. Despite being created by pop giants Lennon and Nilsson, Pussy Cats is far from a pristine record, but it is an epic album that will win the battle of time.

C/S.

I Guess The Lord Must Be In New York City was on the Harry album. Another masterpiece, not mentioned.