«We Honored Our Name». An Interview with Ricardo Cárdenas of Los Versátiles, One of Mexico's Best Kept Musical Secrets from the '60s

León is a city in the state of Guanajuato, right at the heart of the Central Mexican Plateau in the region called El Bajío (The Lowlands). It is, as of 2015, the fourth most populous municipality in the Mexican Republic. A working town with a large leather industry, it has more recently opened up to cultural tourism—taking advantage of its proximity to Guanajuato and San Miguel de Allende— with the creation of new festivals, congresses and expos for both national and international audiences.

As any other large city in the world, Leon has had its share of struggle. Even if the state of Guanajuato was the cradle of Independence, the Cristero War in the 1920’s and the consolidation of an industrial middle class turned the region more politically conservative. That started to wane in the 1960’s, although it still has the reputation of being one of the more conventionalist sectors in all Mexico.

In that agitated decade —one that included the Tlatelolco Massacre and the Olympics, both in Mexico City, 230 miles apart—, Leon seemed to finally open up to the possibilities of modernity. The preceding years had been a constant tug-of-war between provincial tradition and the emergence of new life dynamics. Among these was youth culture, which manifested through music, fashion, and behavior, an example being the "rebels without a cause", as the leather-clad rock’n’roll youngsters were called in a clear reference to James Dean’s film. This phenomenon, though gradual, represents a significant aspect of the region’s history that needs to be explored in greater detail.

Rock music, which made its way to León in the late 1950s through records imported from Mexico City or the United States, was initially a domain of the middle class. A certain level of economic means and education—such as knowledge of English—was required to enter this world. Over time, rock music became more accessible: by the 1970s, it was part of the linguistic landscape of a significant portion of the youth population, and by the 1980s, it was an essential part of the cultural consolidation of working-class youth.

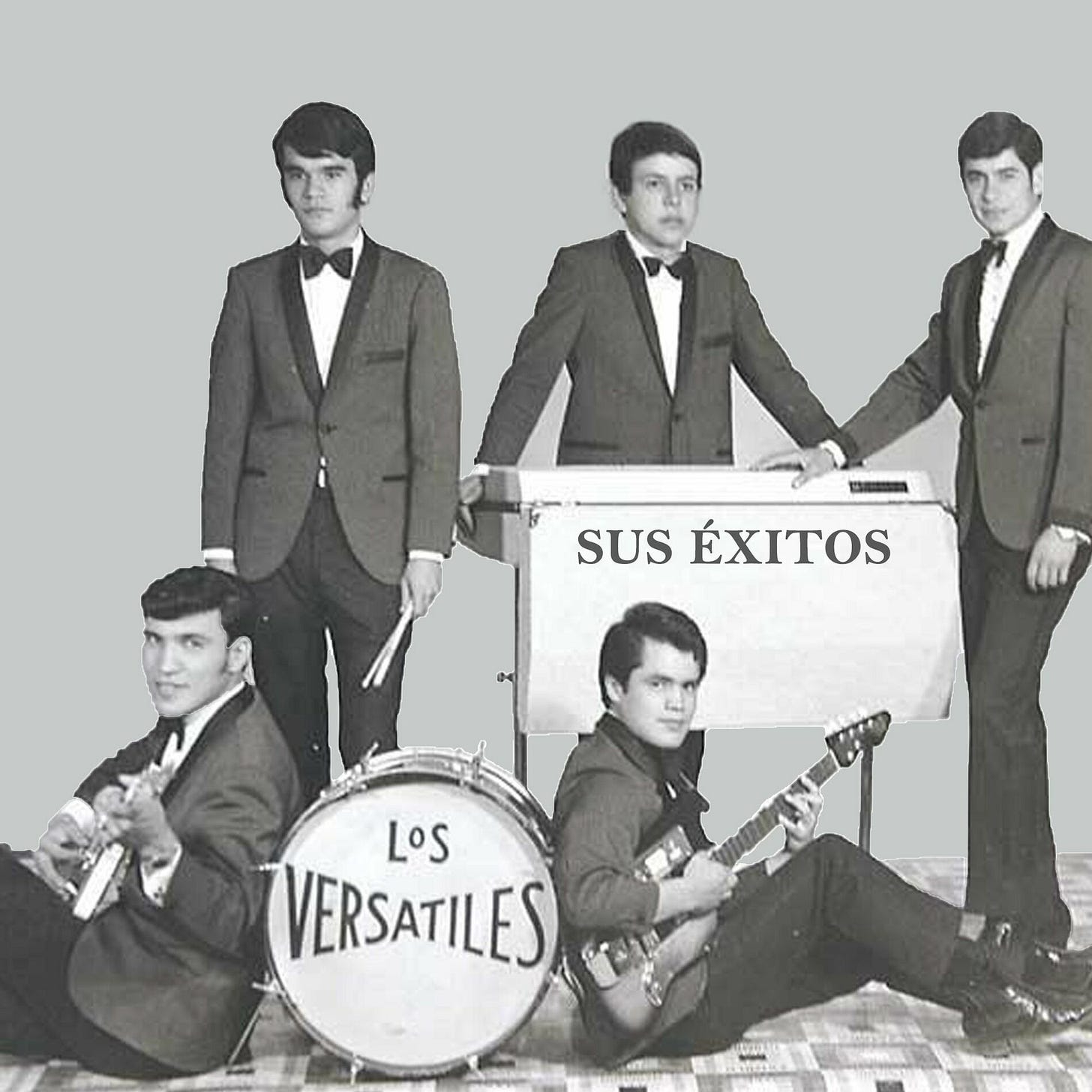

Los Versátiles (The Versatiles) were one of the groups that paved the way for the emergence of a local form of pop music and culture. Formed in 1966 as a student band, by 1968 they had evolved into a rock group—with electric guitars, an electric organ, and drums—and had mastered the genre to the extent that they could adapt it to local sensibilities. Their natural habitat was dances (held at venues like the Rotary Club, the Lions Club, or at bars, restaurants, and nightclubs), tardeadas (small afternoon parties usually organized at private homes), and municipal events showcasing local talent.

However, they soon expanded to other venues, and signed by Discos Musart, one of the largest labels in Mexico, became the first rock band from León to commit their music to tape. In 1969, the band released two seven-inch singles, three EPs, and one full-length album. Their success was a result of their talent combined with good fortune. Their music became well-known in the Bajío region and today, thanks to the Internet, it has reached many more places where it is listened to and appreciated.

The group continued until the mid-1970s, when each member went their separate ways. However, their records and music became part of a history to which bands like Los Free Minds, Conejo Ficción, Undersun, and others would soon add their contributions. An essential part, so to speak, of the soundscape of Central Mexican pop.

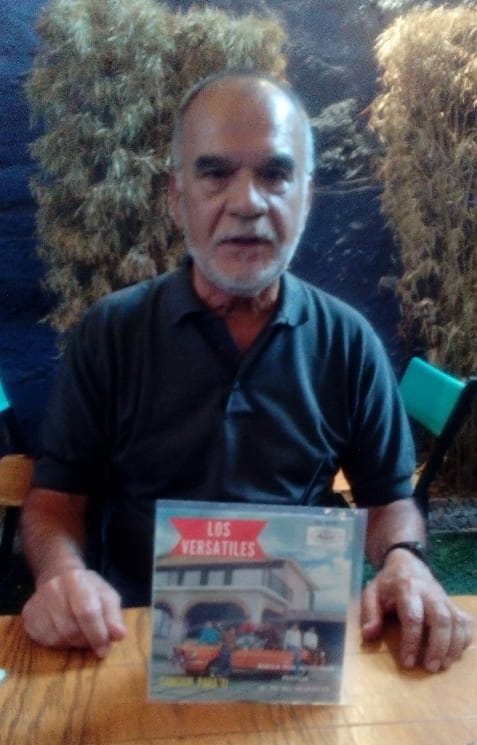

Ricardo Cárdenas (born 1949) was the drummer and percussionist for Los Versátiles for most of the group's career. As of this publication, he is one of the three surviving members of the band. Willing to share his story about his time with Los Versátiles, we interviewed him in June 2022. From here on, we focus on his account.

The Beginnings

My home was very conservative. We were seven siblings: four girls and three boys; out of all of us, I was always the wildest. We were instilled with the arts, yes, but also with prayer. We said the rosary every day. I lived in El Coecillo, one of the oldest and more traditional neighborhoods in Leon. One time, some friends arrived on motorcycles for a posada, a pre-Christmas celebration. My mother said there would be no party until they came in to pray. So, we all went and said grace.

I attended Instituto Leonés, a long-established, very strict institution. From elementary school, I was in the school band, starting as a mascot and gradually moving up. I went through all the ranks and ended up as the band commander. That’s where I learned percussion and developed my musical sense.

Then came the estudiantina, a traditional student band that carries on the 19th century Spanish tradition of song. Those were the times. I played the tambourine and I was nicknamed Yesenia, after a gypsy character who also carried a tambourine in a famous soap opera. That’s how Los Versátiles were born: at first, we were eight, and Miguel Darío Miranda, who later became a goalkeeper for León FC, played the maracas. We started playing at family parties. It was an interesting group because we had members from all social classes. We did it for fun—and for the girls!—and slowly began to take it more seriously. It was 1966. We rarely got paid, but when we did, we saved up to buy equipment.

That’s how I got my drum kit. It was a Ludwig, just like Ringo Starr’s, even the same color. We had it shipped from Mexico City, from Casa Veerkamp, a great music shop. The group started to change, and eventually, we were down to five: Pepe Chuy Cervantes on vocals, Alfredo Cordero on the organ (he used to play the accordion), Mario de Alba on bass, Pepe Mendoza on the lead guitar, and myself on drums.

Los Versátiles

We were pioneers in Leon. Of course, there were many groups before us, and some of them were really good. Los Versátiles played rock, but also many other rhythms. Alfredo Cordero’s uncle was Father Ulises Macías, a highly respected priest in town. His sister, Graciela Macías, listened to us and said that we were “very versatile.” We had no idea what that word meant. She explained that it meant we could cover many styles and switch from one to another. And so, it became our band’s name. Later, there were other, much more famous bands called Los Versátiles, but we had been using the name since 1966, when we were a large ensemble.

We had a stint at the Ladies Bar in the very fancy Hotel Condesa in 1967. That’s where Francisco Moreno, the owner of Calzado Frisco, one of the largest shoe factories in Leon, heard us for the first time. By 1968, we were an electric band with five permanent members. We got two identical Fender guitars. Alfredo already had an organ. We played mostly at dances, afternoon events, and parties. For instance, the Faculty of Architecture of the Guanajuato University organized quite lively parties! They were mostly smooth, although there were occasional fights. If two people were arguing, they’d go to the garden, and the rest of us would surround them. If someone fell, we had to wait for them to get up. And it was all handled with bare hands. It didn’t happen often, but it did happen. Times were different then.

We have many great stories from our gigs. That’s what mattered for us: playing live. For example, there was this guy that some people called “El Niño del Hielo”—The Ice Kid—because he would arrive dressed in overalls, carrying a block of ice, so they’d let him in without asking further! Once inside, he’d leave the ice in the bathroom, take off the overalls, and underneath, he’d be wearing a suit. That was his strategy to sneak into parties and dances; we never knew where he got the ice from but he pretended to be delivering an order. I wish I could remember his name!

One time, when Carabela motorcycles—a Mexican brand made popular in those times with people who couldn’t afford a Harley Davidson—came out, we got a few and rode them onto the stage. We made them roar and made a grand entrance. They were mini-motorcycles, but we used them to impress. Anything went.

The Group Solidifies

Los Versátiles had many strengths. For example, Mario was very good with languages, and thanks to him, we were able to adapt songs from English to Spanish. Pepillo, on guitar, was excellent with arrangements and had an incredible ear. Alfredo, because of his family, had access to many resources and opportunities. Pepe Chuy was charismatic and handled public relations, made connections. And I always said yes to everything, always.

We practiced a lot, as if we were professionals. We covered a vast number of songs and had a very extensive repertoire. We played everything. We were versatile!

The Beatles were a crucial influence for us, as they were for everyone. We even had our own Paul McCartney: Alfredo resembled him a lot and even had a Beatle haircut. He had his own following! Pepillo came up with the arrangement for “You Won’t See Me,” and we played it instrumentally. It’s one of the songs we recorded. Also, Francisco Moreno traveled a lot to Europe and brought us records, so we got to hear new songs—Beatles or otherwise—before anyone else in town. But, most importantly, we played them before anyone else. I remember he brought us Rocky Roberts’ single, “Sono Tremendo,” and we started playing it right away. We were the first. Additionally, we always tried to dress well. We watched the fashion trends around us and copied them, but we tried to stay one step ahead.

The Recording

It was crucial that Francisco Moreno heard us and liked us—and became a manager of sorts. He was a local entrepreneur knew the Acosta brothers, the main bosses at Discos Musart. That was a big deal. I don’t remember exactly how the label got in touch with us, though I think came to see us here in Leon to check us out live. The point is that in 1969, Musart hired us to make a record and took us to Mexico City.

We stayed there for about fifteen days. They put us up in a hotel and everything. We recorded live, with only the vocals done separately. I experienced something unusual for me. When I arrived at the studio, they put me behind a panel like the ones in a bullring and gave me headphones. I could hear even my own breathing with them. I struck the snare drum and it echoed in my ears—quite overwhelming! I couldn’t believe it. We were the first band from León to record professionally, signed by a record label.

We recorded twelve songs, all with our own arrangements. There’s the version of “Sono Tremendo,” the one for “You Won’t See Me,” a Doors cover (“Hello, I Love You”), and other instrumentals. There were also some original tracks.

On the EP covers, we’re outside Don Alfonso Sánchez’s house, the owner of Calzado Destroyer, another huge shoe factory in Leon, around a car that belonged to Francisco Moreno. It was a grand house located at what, at that time, were the confines of the city. Now it is part of Leon’s downtown!

Tours, Celebrity, Pop Masses, and Javier Bátiz’s Scolding

In June 1969, Francisco Moreno took us north. We went to Juarez to play at a graduation or something like that, and we took the opportunity to perform at a Catholic mass in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas. We had already done something similar here in Leon; we were the first to play at the San Judas temple in La Andrade, an upper middle class neighborhood. It was liturgical music, but only the lyrics, because we wrote and arranged new music in our pop style. With the acoustics of San Judas, it sounded very good. In Nuevo Laredo, we played another “youth mass,” as they called it. It was a success. I think we were the first band to play with rock instruments in a church here in Mexico.

At that time, we also played in the beach enclave of Manzanillo. It was very exciting because as we entered the city, there were banners that read “Welcome Los Versátiles.” We were there to play at the coronation of the City Queen. We stayed in a hotel downtown. In the afternoon, they set up a fenced path from the hotel entrance to a stage in the main square; people were gathered around, and when we came out, they screamed and cheered us. We felt like pop stars.

The first performance was for the people. Later that night, we played at an elegant, private party for the authorities and the elite. The next day, more relaxed, we went to the beach, although we brought along some guitars and drums. Once there, we started playing for fun, and before we knew it, we were surrounded by people again. So, we played, so to speak, three times in Manzanillo.

By the way, although the record sold very well in Guanajuato, it reached number 1 in Merida, in southern Mexico. And we had never even been there! We were big there. By a twist of fate, I ended up in Merida many years later working with the Mayas, the local basketball team. But back in the days of Los Versátiles, it was quite surprising to reach those far away places with our music.

There are many other stories. I remember one at the Lions Club in Leon. We were playing with Los Dug Dug’s and Javier Bátiz, two of the greatest legends of Mexican rock. Bátiz was Carlos Santana’s mentor, so go figure. I thought it would be a good idea to smoke, you know, smoke. I was told that not only would I hear the music, but I’d also see it. I gave it a try.

I didn’t feel anything at first, everything seemed normal. When Bátiz finished his set, it was our turn. I sat at the drums, picked up the sticks, and as soon as I counted one-two-three, I felt something pulling me down. Like I was being sucked in. I got scared. I tried to calm down and tried again: one-two-three and, bang, I felt like I was being pulled down again. I couldn’t play. They took me aside, got me to another room, and laid me on the floor while Bátiz went back onstage. When he finished, he came over and spoke to me. “What did you take?” he asked. “Just a Cubalibre, nothing special,” I said. “Don’t be an moron! What did you smoke?” he pressed. I didn’t dare to tell him. Until I finally did. “I knew it!” he replied. “How are you going to see the music, you idiot? Come on! Don’t do that, especially before playing.” Javier Bátiz, with his wild hair as we saw in the photos, scolded me. That’s on another level. Since then, I’ve stayed away from smoking that stuff. When I’ve been invited, I remember Bátiz and just say no.

In the end, we did manage to play, but it was a struggle! And, considering everything we went through, I neved did any drugs again. Who knows how it would have turned out.

The End of an Era

My time with Los Versátiles ended in 1973. I suffered a car accident. Fortunately, I wasn’t injured, but it changed my life. They continued for a few more years, with some changes in the lineup, especially because Musart wanted Pepe Chuy as a solo singer. They even changed his name: Claudio. “Claudio from León.” The contract required him to live in Mexico City, but he would come and go. Los Versátiles finally disbanded around 1978 without having recorded anything else.

From then on, I did a bit of everything, from odd jobs to great ones. It’s always about saying “yes.” I had both good and bad experiences, but I generally managed to move forward. I was a manager at various bars and nightclubs. I worked in public relations. I moved into bureaucracy and served at the municipal, state, and federal levels. I always met a lot of people and had contacts for everything. I am versatile for life, in life.

As a band, we honored our name. We said yes to everything and played a good range of styles. Most of all, we learned a lot. We wrote our own story. I am glad people—young people—are starting to discover us, even if it we happened a long time ago.

Today, I’m past 70 years of age, having lived a fulfilling life. No one can tell me otherwise because I lived it. I truly lived up to the name: I’m versatile. Life passes quickly. Everything ends. But, as we say here, lo bailado nadie te lo quita: what you already danced, no one can take away.

No one.

C/S.