Mel Brooks is something special. His work is a brilliant blend of cultural pride, historical insight, sharp satire, and unabashed silliness. His filmography, though brief, is deeply influential and can be seen as a continuous exploration of cinema’s potential to subvert the world’s workings in favor of the underdog. In this and other ways, there is an Old World yiddishkeit running through all his films, as if it were the blood in his veins.

Born Melvin Kaminsky in Brooklyn to a family of Eastern European origin, Mel Brooks not only honored his roots—he gave new branches to Jewish humor, storytelling, and self-perception in the 20th century. He never hid his Judaism or his Jewishness; on the contrary, it is embedded in his characters, his themes, and his jokes, sprinkled with shtetl tales, biblical references, expressions (and subversions) of tradition, and even allusions to the still-so-recent Holocaust. And these aren’t mere aesthetic choices—they are a vital part of a rebellious discourse that affirms the value of life in an age of cynicism, materialism, and hate.

Beneath the chaos, madness, and silliness lies a real philosophy—one that says laughter is survival. Brooks worked from the idea that if you could reduce Hitler to something laughable, then you had already won. Always aware of the trauma of history, his insistence on joy, connection, and resistance through intellect—in this case, in one of its highest forms: laughter—is a serious matter. There’s Talmudic wisdom in this. He turns suffering into comedy not to minimize it, but to master it.

His impact on American comedy was seismic. His very name conjures up images of outrageous characters, anarchic energy, and an unstoppable avalanche of jokes in every register—almost always loud, explosive, and absurd. But to reduce him to “just comedy” is to miss the heart of his genius. Behind the vaudeville sparkle and variety-show theatrics—an area in which American Jews made their mark—and slapstick chaos, there’s a deep spirit drawing from the well of tradition. Brooks turns laughter into memory, into ritual.

His work is soaked in irreverence that, nevertheless, never eclipses a profound devotion to the culture, history, spirituality, and stubborn joy of Jewish life. It’s this tension—between the sacred and the profane, wisdom and madness—that defines Brooks as an artist. He mastered the mix of high and low, the sophisticated and the crude, the polished and the outrageous. Blazing Saddles (1974) features fart jokes right alongside razor-sharp commentary on the racial foundations of the United States. Because it was never just about making people laugh—it was about showing them that a good belly laugh can be subversive, healing, even holy.

🎭

To understand Mel Brooks the Jew, we must begin where Judaism begins: in family, memory, and tradition. And, inevitably, in loss. Brooks grew up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in an apartment complex surrounded by yiddishkeit—the flavors, language, rhythm, and worldview of Eastern European Jews transplanted to the New World. His father, Max Kaminsky, died of tuberculosis when Mel was just two years old. It’s a loss he rarely spoke of directly, but its shadow can be sensed in his work: there’s an obsession with death, reflected in reverse by his embrace of absurdity as a lifeline.

Mel Brooks was an angry, small, Jewish, fatherless child—a combustible mix fueled by a razor-sharp wit. He found refuge in humor, particularly the kind that developed in the vacation resorts of the Catskills—the Borscht Belt—where Jewish comedians like Sid Caesar, Buddy Hackett, Jack Benny, Woody Allen, Mort Sahl, Zero Mostel, Carl Reiner, Bea Arthur, Jerry Lewis, and Lenny Bruce thrived. But more than names, it was a specific style of comedy that flourished there: neurotic, self-deprecating, fast-talking, and laced with corrosive passive-aggressive banter. A distinctly American Jewish art form.

Brooks got his start writing jokes for Sid Caesar, in a high-pressure, fiercely creative environment where the writing team constantly tried to outdo one another. Even then, Brooks stood out for his manic energy and the way he infused aggression with wisdom. He already carried the soul of the shtetl storyteller—the man who tells a joke to survive a pogrom, who mocks the rabbi not out of disrespect but as a way of loving God through doubt, questioning, and laughter.

🎭

There’s an old saying: “As long as there’s suffering, there will be humor.” Mel Brooks inherited that legacy and pushed it into new territory. He understood that comedy could be both shield and sword. This wasn’t a new idea—many before him, also notably Jewish, had wielded it in cinema, from Groucho Marx to Jerry Lewis. Because language, when used with skill and purpose, can protect the psyche—but it can also strike at power, expose it, reveal that the emperor has no clothes. Humor, like poetry, dares to go—through words—where the imagination hasn’t yet ventured, or fears to tread.

Few scenes in modern cinema capture this better than the one in The Producers (1967), where a desperate Broadway producer stages a musical titled Springtime for Hitler. At first glance, it’s scandalous—that’s exactly the point: Nazis singing, goose-stepping chorus lines, Busby Berkeley-style choreography in the shape of a swastika. Beneath this absurdity lies a radical act of cultural reappropriation.

And it’s not as if Brooks experienced the war only through newspapers or radio reports—we’re talking about a World War II veteran. Springtime for Hitler isn’t a provocation or a whim. It’s not scandal for scandal’s sake—one of the great failings of much contemporary comedy, which often seeks discomfort merely for effect. What Brooks aimed to do was subvert a toxic order that caused death and destruction, to lay it bare in all its ridiculousness so it could be confronted—without false reverence or taboo, which only lead to fossilization, oversimplification, and misunderstanding.

It’s not that Brooks reduced Hitler to the level of a clown—it’s that he always saw him as one. Charlie Chaplin thought the same. The problem was that the dictator’s pantomime blinded many people.

In the musical number “The Inquisition” from History of the World, Part I (1981), Brooks turns another dark chapter in Jewish history into a cheerful Broadway-style spectacle. Offensive? Only if taken literally. For Brooks—as for Monty Python—it’s something else: a way to face horror without false solemnity. To laugh at the persecutors is, even retrospectively, to strip them of their power by exposing their intolerant stupidity.

This isn’t just comedy—it’s midrash with jazz hands and sequins. It’s a rewriting of history, a challenge to the idea that only the victors get to tell the story. It channels the Jewish instinct to use laughter to flip authority on its head—to dethrone pharaohs, outwit Romans, mock czars, and deflate Nazis. Talmudic tradition encourages debate and questioning, often laced with irony. The one who wins is the one with the best argument, not the one who imposes it—and even then, it’s a temporary victory, meant to be questioned by those who come next. In Jewish culture, even the sacred can—and must—be doubted. We argue with God; the very name Israel means “one who wrestles with God.” Brooks draws deeply from this spirit: he questions everything and invites us, his audience—not passive spectators but active participants in the farce—to do the same. His laughter isn’t just entertainment—it’s a form of liberation.

🎭

One of the most surprising things about Mel Brooks’s comedy is that, at times—if you squint—it brushes up against theology. He doesn’t just mock religion with a cynical smirk; he uses it as a canvas for a broader, irreverent philosophical inquiry.

Take History of the World, Part I (1981), where Brooks plays Moses descending from Sinai with three tablets—only to drop one and proclaim: “The Lord has given us these fifteen—crash!—ten! Ten Commandments!” It’s a joke, yes, but also a clever commentary on the fragility of religious tradition, the arbitrariness of authority, and the human fallibility behind divine law. Like so many Jewish thinkers before him, Brooks doesn’t see God as untouchable, but as an interlocutor—a target for parody, critique, and sometimes even reproach.

In a way, Brooks carries on, in his own style, the tradition of Job: questioning divine justice and finding something sacred in the absurd. He may not call it theology, but when you laugh that hard at a sketch like his, you may be experiencing something very close to a prayer said with deep kavanah—with intention, with sincere feeling.

🎭

Mel Brooks’s comedy is not just a form of personal expression; it’s a collective balm. Beneath the joke lies a deep commitment and respect for the trauma of the 20th century. His humor doesn’t avoid the unspeakable—it confronts it from a different angle.

The Holocaust looms over much of Brooks’s work, at least through the 1990s, even when it’s not mentioned explicitly. You could say that his decision to mock Hitler in The Producers—and again in the remake of To Be or Not to Be, which he produced—goes beyond mere derision. It comes from a psychological need. Just thirty years after Auschwitz, Jewish audiences recognized and saw themselves in that act. The joke, of course, was never at the expense of the victims—Brooks counts himself among them. The ridicule is aimed at the madness and irrationality of evil, at the bloated theatricality of fascism. He mocks, with biting wit, the very idea of a dictator: strip him of his mystique—and Brooks makes that look easy—and he ceases to inspire fear. And fear is the fuel of totalitarianism.

What Brooks offers is a kind of linguistic, comedic therapy—for anyone, or any people, grappling with historical trauma. Laughter becomes a tool to recover agency. Instead of being crushed by memory, Brooks’s characters barrel through it with punchlines—a raucous defiance that, at the very least, brings momentary relief, but more ambitiously, seeks a deeper catharsis. It’s a narrative technique for piecing together a broken story through the grotesque, the joke, the ridiculous: to steer the plot down new paths, so it can continue to be told.

As much as Brooks preserves, through language and gesture, the Old World that vanished with the 20th century, he also redefines what it means to be Jewish in America. He doesn’t reject assimilation, but neither does he surrender to it. His work occupies what might be called a liminal space: proudly Jewish, yet fully engaged with American and global culture. For him, Moses and Frankenstein are equally important, as are the Last Supper and Hitchcock. He mocks cowboys, aristocrats, Nazis, priests, and politicians alike—but he also embraces a flawed humanity constantly searching for meaning. Nothing is sacred, and yet everything is—especially the right to laugh.

Perhaps Blazing Saddles (1974) is the clearest example of how Brooks interrogates America through a Jewish lens. Yes, it’s a bawdy western, but it’s also a sharp critique—delivered with heavy doses of political incorrectness (how else could it be?)—of racism, myth, and the hypocrisy embedded in the founding of the so-called land of opportunity. The western is the canonization of the myth of colonization, of the conquest of the West, the "triumph" of civilization over barbarism.

Brooks plays a Native American chief who speaks Yiddish—for no other reason than to break every expectation. The joke works precisely because it shatters narrative rules: it refuses to collaborate with the American myth-making project. And in a way, that’s the Jewish-American experience itself—being both inside and outside at once, always observing, always questioning.

In this sense, Brooks often adopts, especially in his most subversive films, the archetype of the court jester—the wise fool who mocks the king and speaks truth wrapped in nonsense. In Jewish tradition, we find the figure of the shlemiel: clumsy, distracted, but good-hearted, with a unique and often more honest view of the world. He stumbles and blunders, yet frequently carries the deepest truths. Scholar Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi calls the shlemiel “the quintessential East European Jewish figure of comic dignity in adversity.” Brooks is a carrier of that tradition, and through his work, he passes it on to anyone bold enough to take it up.

For American Jews, Brooks offered something rare: a path to cultural survival that didn’t demand assimilation, erasure, or apology. He never hid his Jewish identity—he amplified it. He made it brilliant. He made it powerful. And he made it very funny, stripping it of burdens, freeing it from stereotypes, and giving it new ones—on his own terms.

🎭

Mel Brooks is more than a comedian—he’s a mensch. A sacred madman, a divine clown, a living embodiment of the Jewish belief that laughter can heal, challenge, and transform. His work is chaotic, but under the madness lies a deep moral clarity. By mocking Hitler, he offers catharsis. By mocking God, he opens the door to theological dialogue—if you’re willing to walk through it. By exposing the absurdity of existence while embracing it with gusto, he inspires reflection. And by laughing at himself, he teaches us how to be human.

There is a wisdom in Brooks’s humor that acknowledges suffering but refuses to be defined by it. Like all great comedians—and I always think of that suicidal character in Hannah and Her Sisters, who, after watching a Marx Brothers movie, decides life is worth living—he laughs in the face of death. He doesn’t deny it, but he robs it of its sting.

In the end, Mel Brooks is a kind of rebbe in disguise, a Groucho-esque philosopher, a prophet in a robe of parody. Add to that his work ethic, his brilliant stubbornness during the years he was active, his collaborations with friends—based on the idea that if you don’t collaborate with them, you’re collaborating with the enemy—and his creative control that often overrode studios and executives, and what you get is a total creator. It may not seem like it, because he’s a comedian and not a tragedian—but that’s exactly the point.

In the future, we might—hopefully—consider the ones who made us laugh to be our true sages.

🎭

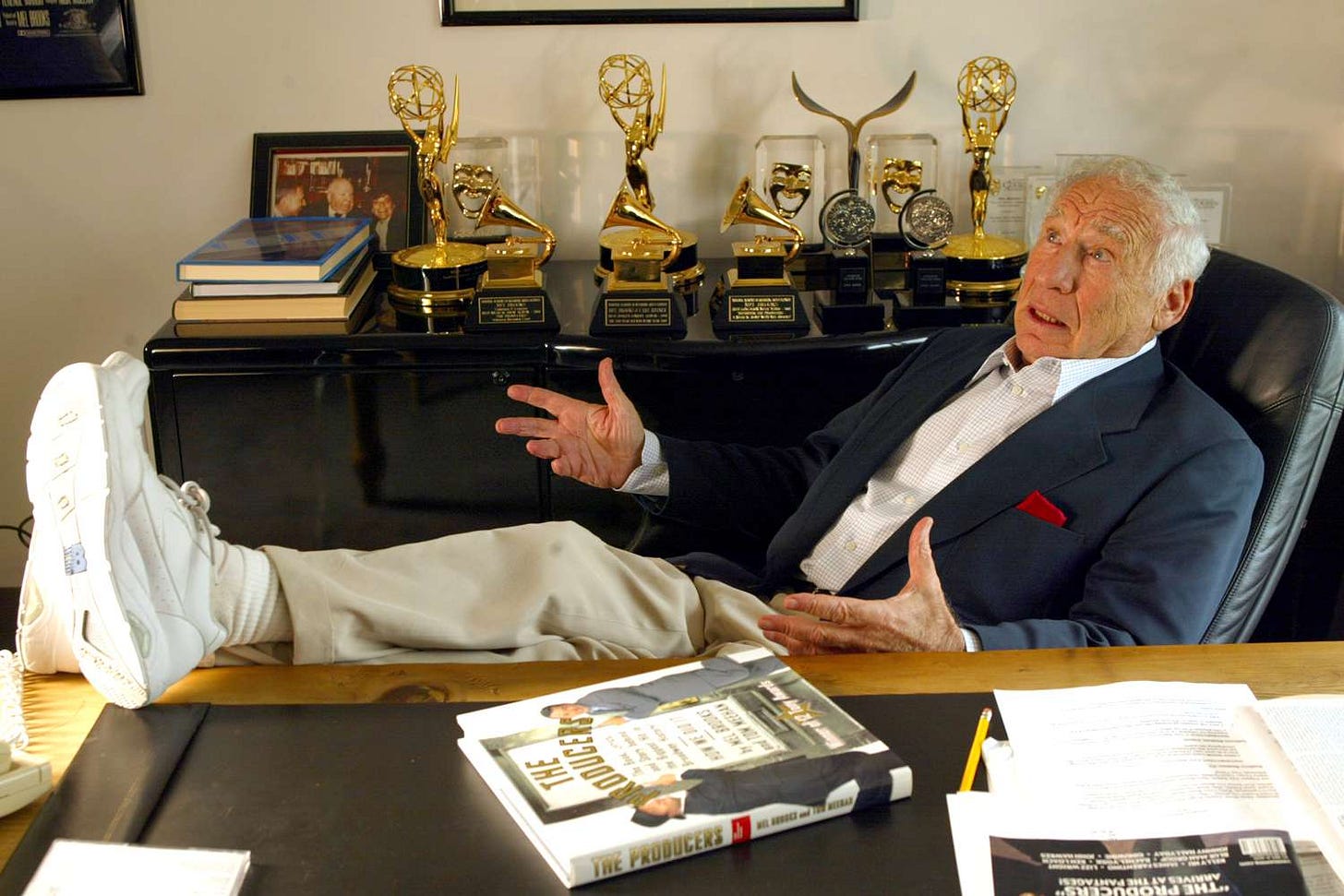

Mel Brooks: A Director’s Filmography, Commented and Considered

A brief exercise in appreciation; only films directed by Brooks are included, so titles like the 1983 remake of Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (directed by Alan Johnson), his cameos, and his television work (like the classic Get Smart) are excluded—though they’re rich with Brooks’s spirit. Another day, perhaps.

The Producers (1967)

A bold satire about a Broadway producer and his accountant who plot to stage a flop in order to embezzle funds. Brooks, drawing on his Jewish roots, uses the absurd show Springtime for Hitler to mock Nazi ideology and the commodification of tragedy. This film set the tone for his entire career—irreverent and sharply socially aware. A spectacular debut. A peerless comedy. A classic film that, decades later, would become a Broadway classic as well. Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder are dynamite together.

★★★★★

The Twelve Chairs (1970)

More than just a comedy genius, Brooks is a wine connoisseur and a lover of Russian literature. This film is an adaptation of a 1928 novel by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, following a man in search of a hidden treasure inside a chair. A warm film that builds a bridge between modern North America and 19th-century Eastern Europe with bittersweet humor.

★★★★

Blazing Saddles (1974)

In this western parody, Brooks takes on racism head-on, casting Cleavon Little as a Black sheriff in a racist town. Its daring humor and fourth-wall-breaking serve as biting critique of American injustice, and reflect Brooks’s commitment to challenging prejudice through comedy. One of the greatest film comedies ever. Perhaps the film that finally shattered the western genre. Co-written with Richard Pryor, with a superb Cleavon Little and Gene Wilder at his best.

★★★★★

Young Frankenstein (1974)

A loving and irreverent tribute to classic horror cinema. Brooks masterfully blends homage and parody. Mary Shelley and James Whale might not have approved—but they would’ve laughed themselves silly. A masterpiece. A peak of cinema made out of love for cinema itself. Gene Wilder is extraordinary, Peter Boyle is perfect, Marty Feldman shines in a tailor-made role, and the trio of Teri Garr, Cloris Leachman, and Madeline Kahn is pure brilliance.

★★★★★

Silent Movie (1976)

A terrific concept. At times it feels like the whole film builds up to the gag of Marcel Marceau delivering the only spoken word, but the script never lets up. Brooks spent much of his career not just parodying cinema’s genres and history, but celebrating them. In a way, this is an artist pointing future historians toward where to look if they want to understand civilization through its cinematic arts.

★★★★

High Anxiety (1977)

A Hitchcock spoof that delves into psychological thrillers. Brooks’s performance as a psychiatrist reflects his comic take on figures of authority. The film explores paranoia and control—subtly touching on themes of oppression and survival. Hitchcock himself gave it his blessing.

★★★

History of the World: Part I (1981)

A comic journey through major moments in history, where Brooks uses satire to highlight the absurdities of the past. His portrayal of Moses and others reveals both his Jewish heritage and his gift for blending historical knowledge with comedy. A series of brilliant sketches that form a hilarious whole. Similar in tone to The 2000 Year Old Man, his collaborative project with Carl Reiner.

★★★★

Spaceballs (1987)

A sci-fi parody that skewers Star Wars, infused with Brooks’s signature humor, full of scatological jokes and politically incorrect gags. Perhaps the start of a decline—hugely entertaining but ultimately lightweight. The spiritual grandmother of the Austin Powers films.

★★★

Life Stinks (1991)

A good idea, poorly executed. Brooks plays a businessman who bets he can survive on the streets without money for a month. Not a parody, and the humor is more subdued. Still, it’s a tender film, showing a humanist and warm-hearted Brooks.

★★★

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993)

A parody of the Robin Hood legend showcasing Brooks’s ability to mix slapstick with satire. His cameo as Rabbi Tuckman adds a personal touch, bringing his Jewish heritage into medieval England with a literal cutting edge. Fun, wild, and joyfully anarchic.

★★★

Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995)

Brooks’s final film as a director. After this, he shifted toward musical theater. It leaves us unsatisfied—not because it’s terrible, but because it’s the end. Brooks tackles the vampire genre in a ‘90s film that doesn’t fully tap into Leslie Nielsen’s talent. Clearly, the cast had fun—but the audience, perhaps, not as much.

★★

A laurel and hardy handshake for an excellent piece

12 chairs is a gem. Thanks for this excellent read.