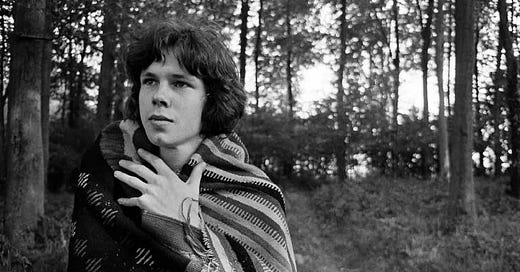

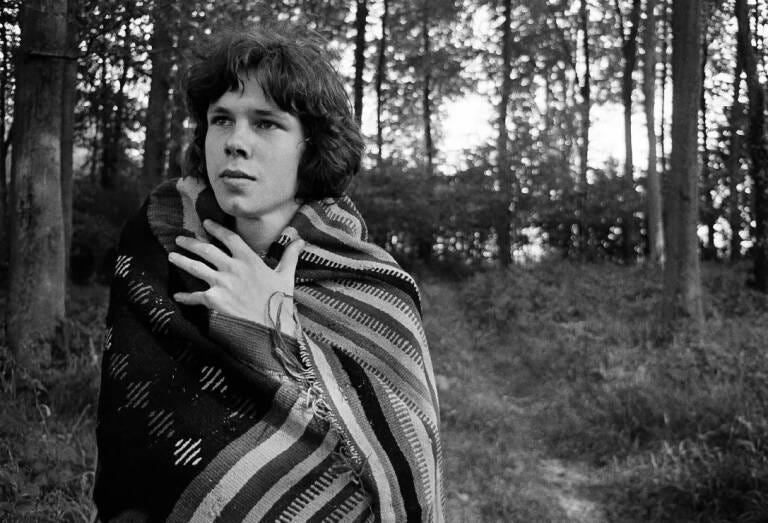

Nick Drake, This World is Not for You. A Biblical Exploration of the Musician and Poet 50 Years After His Death

In the small town of Tanworth-in-Arden, in the county of Warwickshire, in the heart of England, lies the St. Mary’s cemetery. Among many gravestones, one reads: Now we rise and we are everywhere. Here rests a man like so many others, magnificent and brilliant, named Nick Drake, who, unlike those around him, left the world a legacy of songs.

Nicholas Rodney Drake (1948-1974) is an artist who seems set apart from all others, almost his own genre. While we can place his career within the context of the pastoral English folk movement of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, his life and work are those of a tragic Romantic figure from the 19th century, or perhaps a male version of Esther Greenwood, the protagonist of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. In the context of the pop era, we can say that Nick Drake is iconic for the influence his music has had on other musicians and those in the know, but he is far from being part of the collective consciousness of the modern song heroes. Although his albums fit perfectly alongside those of Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Fairport Convention, Carole King, Van Morrison, and even The Beatles, his music is even more intimate, claustrophobic—a type of song that is both unsettling and spiritual. He should be understood as a sculptor or painter whose life is entirely devoted to a work that, only after the artist’s death, finds its place in the vast history of things. Because, perhaps, as life and work are one and the same, they must merge into a single entity, and thus, one part had to burn…

He was born in Burma to aristocratic parents but grew up in a traditional family country house, where poetry was read, tea was drunk, and the piano was played, all in an England whose foundations had been shaken by the beat groups, the new and whimsical culture of Swinging London, psychedelia, and rock. But at the heart of the family dynamics was art, and there was great tolerance for any expression of creative spirit. His father, Rodney, was an engineer who had traveled and made his fortune in the colonies; his mother, Molly, wrote poetry and songs that she sang to her children while sitting at the piano in the living room; his sister, Gabrielle, found in theater a reason for her open and cheerful character, studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and later pursuing a career in English television and film.

Nick Drake fell in love with music as a student at the prestigious Marlborough College. He learned to play piano, clarinet, and saxophone; he even joined The Perfumed Gardens, a very short-lived pop combo. But he eventually adopted the guitar as his instrument of choice after hearing Leonard Cohen’s first album, which impressed him with its expressiveness and depth.

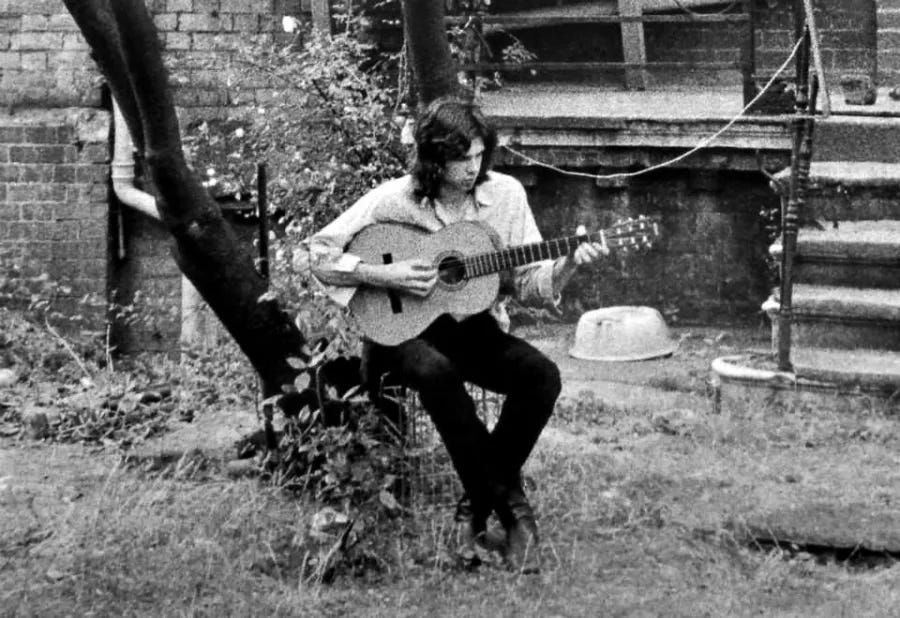

During those years, he traveled to France, where, between Paris and Marseille, he lived as a bohemian, singing for coins, drinking the remnants of glasses left behind on café tables, and experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs; he even met the Rolling Stones during one of these expeditions. When he returned to study at Cambridge, he found himself in a world that seemed alien to him. Although he was athletic and excelled in rugby and cricket, the only thing that truly interested him was music. He had mastered the guitar, placing himself at a level above many of his friends and colleagues, developing a series of strange tunings and a flawless picking technique. His voice and strings merged into a vibrant harmony, and he saw himself on the same level as Phil Ochs, Donovan, or even Baez and Dylan.

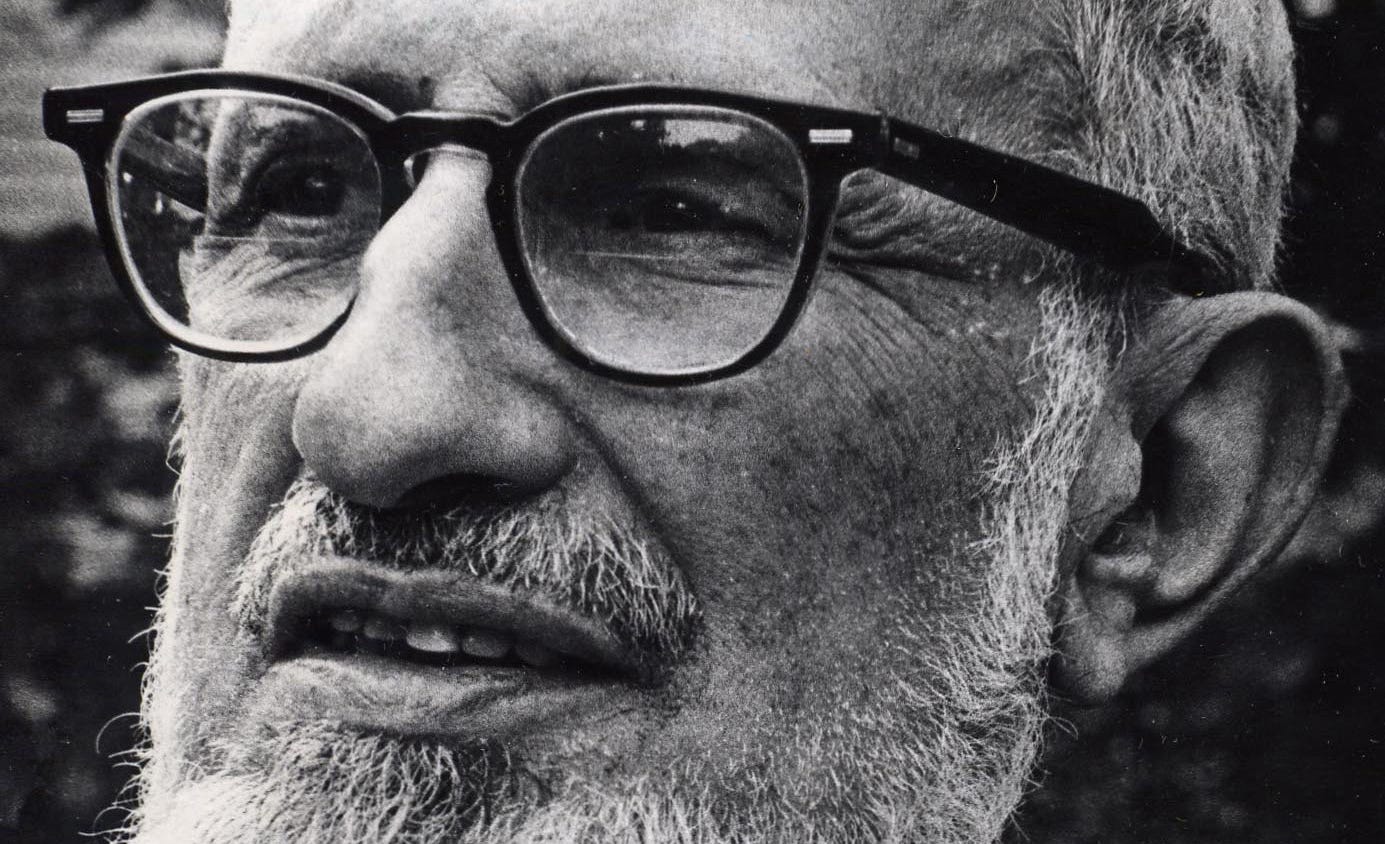

At this point in the story, a crucial figure enters: Joe Boyd. One of the most important producers of the late ‘60s, a strong supporter of folk rock, psychedelia, and cutting-edge recording techniques; he had already worked with The Incredible String Band, Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, and Fairport Convention, as well as other folk, traditional song, and Indian music acts.

Together, they recorded his debut album, Five Leaves Left (July 1969), a stunning record. Composed of simple song structures but complex harmonies, with lyrics full of symbolic poetry, it was recorded to sound as though Nick Drake were in the listener’s room, singing just for them. But with orchestral arrangements by Robert Kirby, the music was transformed into one of impressionistic landscapes. Joe Boyd recalls that Nick Drake would often record his parts in a single take, isolated in darkness, lost in his thoughts and his unusual chords.

At the time, it was a deeply misunderstood album. Its sales were meager. Despite John Peel playing it several times on his influential radio show, the indifference soon turned into frustration. What followed was no better, as Nick Drake's attempts at live performances became a series of long silences or disinterested chatting from the audiences while he tuned and retuned his guitar.

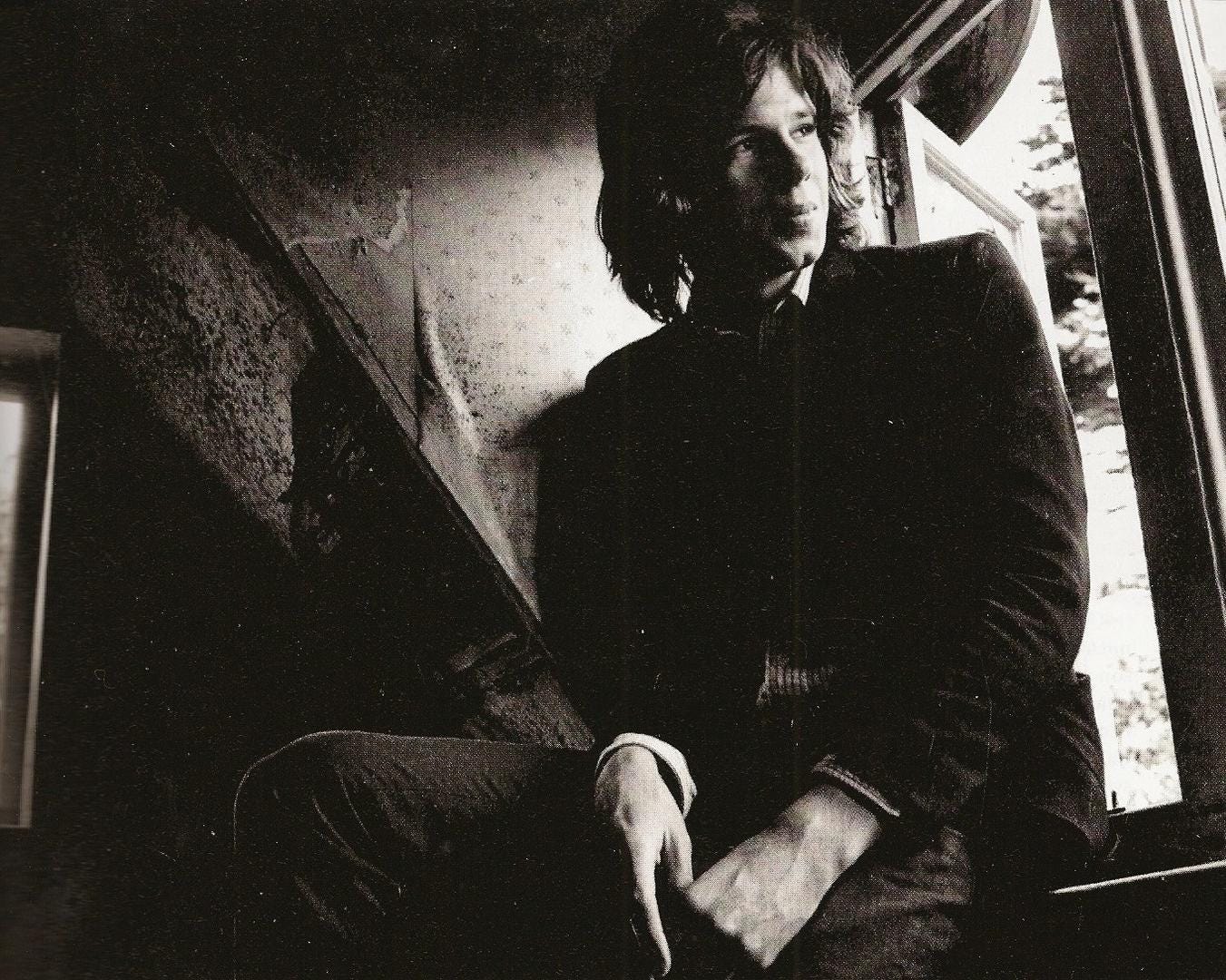

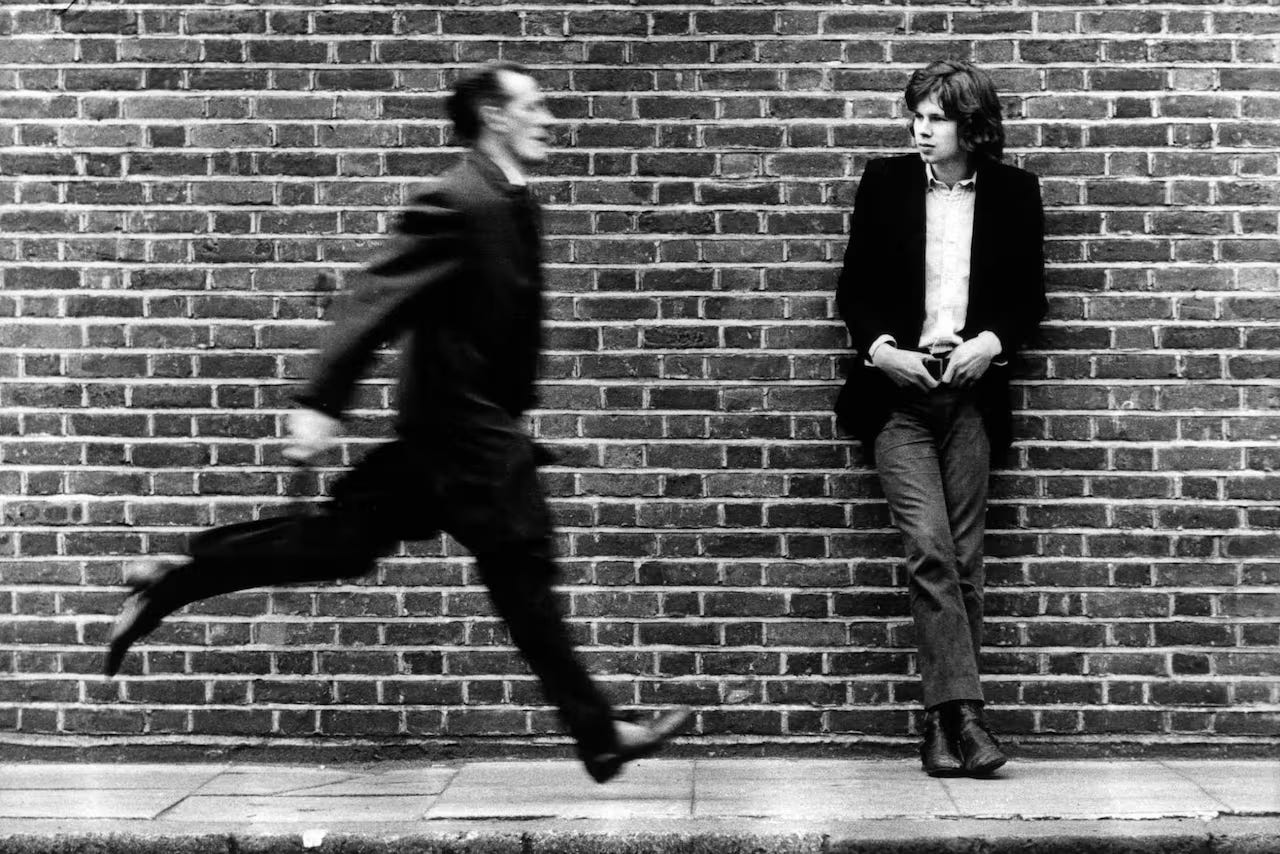

He moved to London around this time, to be at the heart of the musical activity. A new album, Bryter Layter (March 1971), contained songs in the same vein of acoustic folk but with a slightly more elaborate production. The result was the same: a deafening silence from a confused audience. He spent weeks locked away in an apartment, speaking little to some friends—among them Boyd and Kirby—and making sporadic trips to the family home in Warwickshire. During these erratic months, he would sometimes take the car and disappear; occasionally, he had minor accidents on the backroads he drove or would return on foot to the estate, explaining that the car had broken down.

His next work was different. Perhaps his definitive album, Pink Moon (February 1972), was recorded in two nights with sound engineer John Wood, capturing the essence of Nick Drake—just his voice and guitar. The album lasts barely 28 minutes but is both a spiritual manifesto and a material testament. Although Pink Moon did not fare better than its predecessors, Nick Drake was already beyond good and evil. He had recorded his masterpiece at only 24 years old.

He returned to Warwickshire. This can be interpreted as an acceptance of defeat, but there is evidence that suggests the opposite. Nick Drake continued writing and playing, planning a new album; although it marked the beginning of his descent into the void, the slow onset of his death, it was not an inevitable and violent downward spiral. His father kept a diary during these months, noting the good and bad days with a touching stoicism. The days spent locked in his room and the long walks in the garden; the nervous breakdowns and the afternoons in the living room with Molly and Gabriella; the meager royalty checks and the loving correspondence with Sophia Ryde. But in the end, darkness prevailed.

Nick Drake went to his room on the night of November 24, 1974, and closed the door. He was found lying in bed the following morning. The doctors ruled it as poisoning from amitriptyline.

Nick Drake, with his deep sense of introspection, existential loneliness, and melancholic beauty, embodies qualities that align with the concept of Adam II described by the great rabbi and thinker Joseph B. Soloveitchik in his work The Lonely Man of Faith. This archetype represents a man of faith attuned to the existential dimensions of life, who nevertheless faces a fierce struggle with the isolation from which he confronts profound questions about human existence, the divine, and the possible meanings of suffering.

Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993) was one of the great thinkers of the 20th century. Part of a dynasty of distinguished rabbis, he was born in Pruzhan (now in Belarus), which was part of the Russian Empire. His father was a rigorous Talmudist, and his grandfather a notable authority on Halakha, Jewish law. He attended several yeshivas, traditional schools, and studied philosophy at the University of Berlin, where he became familiar with the works of Kierkegaard and Heidegger. His thought, therefore, harmonizes his legacy with modernity; for example, he juxtaposes his deep knowledge of the Torah with the novel biblical criticism that drew from literary analysis and the scientific method. One of the notable results of this exercise is the book The Lonely Man of Faith, whose central argument arises from an interpretation of two biblical passages regarding the creation of man.

When one reads the text, there appear not just one, but two versions of creation, and thus, it seems there are two characters named Adam.

The presence of two Adams in the Bible, which a superficial or biased reading might consider an editorial mistake, suggests things that have already been the subject of scholarly interpretation, both theologically and in other fields. These are two intentional representations, with purpose.

In summary, the two versions of creation in Genesis are as follows: the first describes the formation of humanity as part of a cosmic and universal process; in this account, humans are created in the image of God, male and female together, as part of God’s command. Soloveitchik’s analysis begins with a sharp reading, a confrontation with the text. In this first version, אָדָם (Adam), the first man, is "created in the image of God." In Genesis 1:27-30, he is a character who is both male and female, given the command to be fruitful and multiply, to dominate nature, to shape the cosmos and reduce it to his size, to guard the world in the name of his creator. According to Soloveitchik, this is a functional, even pragmatic, utilitarian, and worldly being. He refers to him, schematically, as Adam I.

In the second version, a detailed and anthropocentric narrative is provided, in which the first man is formed from the dust of the earth; the creation of חַוָּה (Eve), the first woman, comes from a part of Adam’s body. This version emphasizes the personal and relational aspects of humanity’s creation, where humans are given specific responsibilities regarding the care of the Gan Eden, the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2:15). Soloveitchik designates this as Adam II.

The critical theory of the text speaks of different sources or traditions that, from a kind of textual medley, formed the canonical accounts, an early example of intertextuality. But even under this explanation, the fact that both versions coexist within the same flow of the text speaks to an ulterior purpose: to address the complexity of the human condition and its relationship with the divine and with the universe. These are two perspectives that, rather than contradicting each other, complement one another.

Adam II, according to Soloveitchik, is a character marked by loneliness and insularity. He knows his own fragility and recognizes the tension between a quest for autonomy and independence and a submission to a higher, divine power. His exile is not just social but a vast metaphysical solitude, a sense of separation from the world while seeking a connection to something higher, beyond, something that cannot be fully reached because the body itself is, at once, both a means and an obstacle.

Nick Drake's music mirrors this sense of separation, of otherness. His songs are introspective, tinged with melancholy, a lonely engagement with the world, living in constant questioning of his place within it. His songs don’t just address personal suffering; they resonate with an almost universal loneliness, as alienating as it is redemptive, much like the isolation of Adam II. His lyrics and chords, often in rare tunings, paint the picture of a man grappling with questions that have no answers while contemplating the transient nature of life. The great paradox of the man of faith: life is hard, but how beautiful; life is everything, but how brief.

His work and personal life were one and the same. Nick Drake was a very private individual who built impenetrable boundaries around himself, even for those closest to him, while at the same time seeking approval and affection from others. But his world was filled with characters who resembled Adam I: creative, social, with impulses to dominate nature. Nick Drake respected these traits to the point of being intimidated by them, but he could not fully identify with them. It is possible that what his diaries and those of his family—his father’s journal was not abandoned even at the very day of Nick Drake’s death—record as a possible mental illness might be a clinically accurate diagnosis, but not a spiritual one: his disconnection from the world, his expansive melancholy, was pure longing. Longing for something he knew existed beyond the formalities of worldly existence. His inner struggle was expressed through his music—complex, bewildering, magnificent—in an attempt that, to us as more or less passive listeners, seems of unparalleled beauty; for him, an Adam II, they were incomplete and disconnected attempts to express the ineffable.

The tension of Soloveitchik’s Adam II between human freedom and obedience to an external, superior power is one of his great philosophical dilemmas. Adam II is not free in the sense that he can act as he pleases; his free will is defined by his commitment to fulfilling the divine will, of which, in one way or another, he is an instrument, despite not fully understanding it. This is precisely one of the great characteristics of Adam II: he places himself at the service of something greater than himself. The existential weight of this situation results in a paradox: true freedom is found in submission to a higher purpose.

Nick Drake’s work is far from religious, although his imagery and, above all, his central themes could be approached from this perspective without diminishing either his music or the spiritual intentions of such an analysis. This tension between autonomy and the drive to search for something greater is an internal engine of meaning and a fascinating poetic-metaphysical process, for the artist, guided by impulses generated by external forces, uses the mechanisms that belong to him—his talent, his sensitivity, his learning—to try to shape and make approachable this search that can be defined as abstract, though the term does not fully do it justice. And so, his inability to find a clear and absolute place in the world, his rejection of success as understood in the worldly sense, and his pursuit of a depth that can only be reached through severe renunciations, are manifestations of this tension between independence and surrender. Nick Drake’s songs yearn for a place of peace and longing with the certainty that it does not exist.

Soloveitchik’s Adam II recognizes suffering not only as a fact of life but as something that speaks to the deepest realities of the human condition. Thus, he does not flee from suffering—though it still causes him pain—and if he immerses himself in it, it is because he seeks meaning there. It is a profound experience that can open portals to connect with the divine, and therefore, shed new light on the human experience.

Nick Drake’s music directly alludes to suffering. He faces it, embraces it, envelops it. But his songs never sink into despair nor slide into the nihilism of lost causes. On the contrary, they possess a quiet delicacy, a stony strength expressed in a voice that never screams, and in chords that, with unexpected combinations of notes that vibrate with their own light, resonate with a total faith in the power of harmony. Nick Drake thus tells us that, in his view, pain and beauty are inseparable; it is in the ebb and flow between the two that meaning is found, and yet, he cannot explain it to us. There is no answer. But with his music, he opened a portal so that, anyone who has ears, may listen and cross the bridge to the unknown that he had already built. And it was an endeavor in which he gave his life.

The imperfect and the transitory, then, are necessary parts of life. Soloveitchik’s Adam II understands that life is incomplete, that the search must be content with opening new questions, and that definitive conclusions only diminish the understanding of possible meaning. Moreover, the world does not offer, nor will it ever offer, easy answers. We can understand its mechanisms, even replicate them, but its motives remain a mystery.

If there is one adjective that can define Nick Drake’s work, it is “fragile.” There is no orchestration that could support his songs, which move through the ear with the latent threat of collapsing at any moment. And yet, even though they always reach their end—and how many times do they evoke a sigh, sometimes from pure inspiration, but most often from relief, knowing we could close, along with Nick Drake, a small cycle of unfathomable depth which we end up calling, for lack of a better word, “beauty”; the ineffable, precisely—they remind us of the uncomfortable fact that existence is beautiful precisely because it ends. Every work is an unfinished work.

Recognition serves little. But that is another matter: that will not stop the work from being done. The search is not in the finding, but in its possibility, in the steps forward, in the illuminated corners. That is what it means to find. The transcendent seems unattainable. But, isn’t it true that it would stop being so if we could touch it?

One of the most "Nick Drake-esque" songs in the pop canon is Chris Bell's “I Am the Cosmos.” Not so much because of its sonic approach—based on piercing guitars, a rhythm marked by drums, a voice testing its limits—but because it shares the intention of expressing a metaphysical, cosmic loneliness. The certainty of being alone in the universe, yet deeply connected to it. The search for purpose, for meaning, is solitary. Even when Adam II—or Nick Drake, or Chris Bell—are surrounded by beauty, love, and fleeting moments of joy, they cannot help but feel separate from the world; this separation connects them more deeply to it.

I think of Pink Moon, the last album Nick Drake recorded, stripped of orchestrations, a conversation between his voice and his guitar. It seems to me an album in which a sad and brilliant resignation resonates, a recognition that the abyss between the world and his inner self will never be bridged. But at the same time, there is a quiet acceptance, the firm knowledge that some things are beyond human understanding, and that’s okay. Like Adam II, Nick Drake’s journey won’t resolve the tensions, but will live within them. Meaning lies in the struggle, not in the resolution.

In contrast, attempting to place Nick Drake as an Adam I results in a character doomed to his own condition. This biblical figure represents humanity in search of dominance, autonomy, and the achievement of worldly accomplishments, as opposed to Adam II, introspective and spiritually attuned. Only in the notion of Adam I’s condemnation—meaning being disconnected from deeper spiritual truths and trapped in a cycle of existential frustration—does it seem to align with Nick Drake’s tragic life.

According to Soloveitchik, Adam I is a figure defined by his pursuit of domination over the world, translated into achievement and self-sufficiency. He is driven by an inherent desire to shape the landscape and make sense of the universe. In this existential ambition, the individual sees himself as separate from the divine but with the jurisdiction to manipulate his surroundings through intellect and willpower.

Nick Drake, in contrast, was an artist whose creativity and desire for self-expression seemed to arise from internal tension rather than a direct desire to dominate the world. Nick Drake’s struggle was to control his identity and find his possible place in a strange universe. As such, his journey ends in disillusionment and alienation because this world cannot be fully controlled or understood.

Nick Drake's poetic music, filled with longing and melancholy, reflects Adam II's search for meaning, beauty, and transcendence in the face of a confusing world that responds to suffering with a vast, indifferent silence.

In the small village of Tanworth-in-Arden, in the county of Warwickshire, in central England, lies the St. Mary cemetery. There, among many gravestones, one reads: Now we rise and we are everywhere. Here rests a man like so many others, magnificent and brilliant, named Nick Drake, who, unlike those around him, left the world a legacy of songs. Fifty years have passed since his death. And, like all the essential texts, his music is more alive than ever.

C/S.