Finding a New Language. Beatles for Sale at 60

1964 was the year of vertigo. Starting with a stay in Paris in January, their first trip to the United States in February—and with it, the global explosion of Beatlemania—the filming and premiere of their first movie alongside the recording of their third album to accompany the film, a world tour, and a handful of television and radio sessions, the Beatles barely had time to catch their breath.

Beatles for Sale, their fourth album in its original English configuration, was released on December 4, 1964, just in time for the holidays. It was recorded in sessions spread over August, September, and October of that year, amidst one commitment after another. Although it spent 46 weeks in the UK top 20—eleven of them at number 1—it is often, in hindsight, regarded as a lesser album. It’s true that it doesn’t match the prolific nature of its predecessor, A Hard Day's Night, where every song carried the Lennon/McCartney stamp. This time, it was an album produced under pressure in a wild year, squeezing hours out of days: the title of one of its most celebrated tracks, "Eight Days a Week," originally referred to an unrelenting work schedule. It has been criticized for lacking the vitality and brilliance of their previous albums, for being a tired and lackluster record, and some have even had the audacity to call it “the worst Beatles album,” whatever that might mean.

The album, however, is as wonderful as any other from their era, for its own particular reasons. It is filled with interesting moments and is key to the evolution of both the sound and the career of the Beatles. If we view the quartet’s discography as a linear progression, this album marks their first “return to their roots,” a move they would repeat in another time of crisis in 1969 with the Get Back project. Seen this way, it is a project that, despite its rushed conception, takes risks and avoids repeating what had already been done in previous albums.

Later albums like Rubber Soul and Revolver are famous for their sonic experimentation, but while A Hard Day's Night saw the group begin to use the studio as another instrument for creativity, beyond just reproducing their live sound, Beatles for Sale takes a mixed approach. It includes six cover songs from their live repertoire and eight original tracks in which the studio is already an integral instrument. It marks a transitional period for the Beatles, moving from being a live band functioning as a pop group at the mercy of the industry and the public, to becoming studio artists who take control of the industry and present themselves to the public in a new way. It was a revolution in itself. And it wouldn’t have been possible without these intermediate steps.

In Beatles for Sale, there are two key American influences. These are new and noteworthy, as they hadn't been as evident in the previous albums or singles. The first is country and western, a musical and thematic approach from the United States that, however, found a home in Europe, specifically in Liverpool, thanks to its port and the unique character of its inhabitants. All four Beatles grew up with this influence, and it makes sense that, in the city during the band's formative years, there was a skiffle craze—an amateur version of the deep American vernacular sound.

The second influence is folk music. While the term can be problematic, here we refer to a type of music that evolved from traditional American folk songs—Anglo-Saxon, Native, and those from the 19th and 20th-century immigrant waves—which took its definitive form during its second revival in the 1950s and ‘60s. It is, then, a culture of acoustic instruments that emphasizes social, political, and emotional themes from challenging perspectives. Its representatives from the era—ranging from Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs to Bob Dylan and Joan Baez—exemplify this music better than any possible description.

Together, these two influences, combined with the Beatles' pop sensibility, result in a rougher, more direct album, a brutally honest one. The full incorporation of these two styles into the Beatles' language brought emotional depth, as they gave the band the freedom to approach their usual topics from different angles—the love songs now express doubt, heartbreak is no longer the pain of a teenage heart but that of an adult questioning their feelings—and allowed them to speak frankly by legitimizing the darkness of emotions, the importance of the everyday, and the necessity of expression as a means of escape, protest, and exposure of problems. If Beatles for Sale shows that the Beatles have matured, it is the result of their experiences and the acquisition of a language to reflect on them. It is not yet complete wisdom, but it marks the moment when a door opens that leads to different rooms with more doors. Part of what makes the Beatles important is this exploration of possibility. Beatles for Sale is a huge step in that direction.

In this sense, I find the way the last song on A Hard Day’s Night, “I’ll Be Back,” effortlessly connects with the first song on Beatles for Sale, “No Reply,” in both sound and central theme, to be perfect. Introspection and melancholy. A new self-awareness is expressed. The first-person perspective becomes confessional, vulnerable. After exploring various ways of communicating in a pop song, reaching a revolutionary peak with the shift in perspective in “She Loves You,” Lennon and McCartney return to the self to start exposing the scars rather than hiding them. From “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” we move to “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party”; from “I’m Happy Just to Dance with You” to “I’m a Loser.”

The second-person perspective also begins to be used in new ways. It’s no longer “P.S. I Love You,” but rather “What You’re Doing,” a slightly indignant question, a song as intricate as its sense of unease, with Ringo Starr’s syncopated rhythm, George Harrison’s shimmering guitar, and George Martin’s restless piano, all in a Phil Spector style. And although we’re still not seeing an open confrontation—a sentiment whose tropes would later explode and come to the forefront with groups like the Rolling Stones—it does emerge later in songs like “Think for Yourself,” “Run for Your Life,” or the more vulnerable objection in “You Won’t See Me” and “I’m Looking Through You.”

The lyrics take much greater risks, undoubtedly influenced by the vital and musical impact of Bob Dylan, particularly on John Lennon. It’s not just the still candid and raw “I’m a Loser” or the veiled, death-related reference in “Baby’s in Black,” but also the embrace of eloquent, almost surreal wordplay—which worked so well in A Hard Day’s Night—in “Eight Days a Week” and the photographic negative of “From Me to You” (which exudes confidence: "I’ve got everything that you want" in “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party,” which dares to admit things like "there’s nothing for me here, so I’ll just disappear."

There is, however, a fascinating balance in the topics, many of which were written and rejected in the past, only to be resurrected due to a lack of original material. These songs are approached with the musical mastery of Beatles who had been constantly playing together onstage. We move from the desperate resignation of “No Reply” to the nostalgic tenderness of “I’ll Follow the Sun,” rescued from the vault of pubescent songs written in Liverpool, with its sweet vocal harmonies perfectly paired with the Latin-tinged guitars. From the anguish of “I’m a Loser” to the contained euphoria of “Every Little Thing,” a rare example of a song mostly written by McCartney but sung by Lennon; its exultant chorus is enhanced with powerful timpani, yet it expresses far more fragility than self-sufficiency. From the threatening discord of “Baby’s in Black”—a gloomy waltz that, despite or perhaps because of its less-than-perfect performance, turns out dark and somewhat unsettling—to the pop clarity of “Eight Days a Week,” which also makes use of a studio trick, a brilliant fade-in. This was actually the first song by the group to be completed not from rehearsals but through an exhausting studio session, serving as a lesson for future albums: the recording floor as a sound laboratory.

It’s a much more acoustic album, also a result of long travels and hours spent in hotel rooms. New ways of using vocal harmonies, also influenced by country music, appear, such as the choruses in “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party.” It’s clear that Beatles for Sale was attempting to take new directions. A Hard Day’s Night was the pinnacle of pop. Trying to repeat that formula would have made commercial sense, but not an artistic one. The old songs that had once been rejected were now given a new life and personality. In most cases, it worked: all songs are recognizably beatley, even if they are not sparky anymore.

It is, of course, a transitional album. But it’s a little bit more than that too. Taken on its own, it’s an album that foreshadows trends like folk rock, the blending of pop and country, the confessional songs of the Laurel Canyon musicians, the widening scope of rock songs, and the boldness of confronting less prudish themes through an admission of vulnerability, which would later transmute into the sophistication of pop.

In Beatles for Sale, however, there remains a simplicity that keeps the Beatles young and accessible. Teenage audiences still understand this language, though it’s beginning to bewilder them. The road to “Yesterday” and the complete acceptance even by audiences outside their age and sensitivity is being paved. And, of course, step by step, the complete revolution of culture is being built, one that would become undeniable with the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the elevation of the Beatles from pop idols to a global cultural heritage. Overcoming Beatlemania meant taking steps that could alienate fans, but that’s an inherent cost of any venture undertaken.

Beatles for Sale is the last album to feature cover versions. This is partly due to time constraints, as well as the fact that two songs from this period, “I Feel Fine” and “She’s a Woman,” were released as A and B sides of a single in November 1964, which, according to a commercial policy that was strictly applied to the English market, disqualified them from being included on the album. Unlike with With the Beatles, George Harrison does not contribute any original compositions.

However, in a period when live tours were a central part of the Beatles' artistic life—and indeed, of any pop act—it was fitting that they included songs by other artists that had been part of their repertoire since their days in Hamburg and at The Cavern. In the cases of Chuck Berry’s “Rock and Roll Music” and Buddy Holly’s “Words of Love,” two of the Beatles’ most significant musical and spiritual influences, the band makes these songs their own. The former is an explosion of energy, while the latter is a splendid display of guitar work, even though it was recorded by a band already exhausted and eager to go home. Carl Perkins, a major influence, is honored in “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” a baffled and fun commentary on the realities of Beatlemania sung by George—the biggest critic of the phenomenon, who would later mock the term “fab” used by the press to describe the band—and the less fortunate “Honey Don’t,” sung by Ringo. While Ringo’s energetic shuffle on the drums matches the country mood of the song, it fails to lift it from its monotony.

The two remaining covers are vocal showcases by McCartney and Lennon, respectively. “Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” successfully blends a rhythm and blues standard by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller with one of Little Richard’s raucous songs, which Paul was so good at performing. Though it doesn't quite reach the triumph of “Long Tall Sally,” it’s a joyful and bouncy tune with a call-and-response structure that the Beatles had mastered, so much so that they managed to record it in a single take; there was a second one, but it was just for backup and wasn't used.

The case of “Mr. Moonlight,” originally by the raw-voiced pianist Dr. Feelgood and the Interns and written by Roy Lee Johnson, is less successful. A B-side that demonstrates the Beatles' deep knowledge and respect for the music that shaped them, it never quite takes off, despite John Lennon’s astounding vocal effort. The arrangement, which isn’t entirely muddy and bluesy, nor openly Latin, sounds odd to the ear and fails to gain power or expressiveness, despite the interesting isolated elements: the vocals, exotic percussion, and a muffled organ. The Beatles had been playing “Mr. Moonlight” live to open their shows since 1962, but the studio recording of the sessions fails to capture the excitement and exoticism it likely conveyed in concert. Once again, taking risks means falling into the void without a safety net.

Also left off the album was a reworked version of Little Willie John’s “Leave My Kitten Alone,” which may have better suited the rock'n'roll character of the covers on Beatles for Sale. This track almost became one of the main attractions of Sessions, a project that emerged in the 1980s to include unreleased material from the Beatles' recording sessions, but that was ultimately canceled. Its final mix wasn’t known until 1995, when it was included in Volume 1 of the Anthology series, where it became one of many rarities officially released by Apple Records.

Beatles for Sale was produced during a time when the music industry operated very differently. The concept of a consolidated pop group did not exist; viewed as ephemeral, a seasonal product, the loyalty of the public was not taken for granted. It was necessary to maintain media presence with new products, concerts, radio and television appearances, and by the '60s, even conquering cinema. For the Beatles, 1964 was the busiest year of their lives. The irony tinged album title says it all.

The four were, as Paul McCartney titled his 2023 photo book, "in the eyes of the storm." While they were deeply immersed in the industry's dynamics, their experience was unprecedented. There had been nothing like it before. Much of the whirlwind year was the result of both Brian Epstein’s and the Beatles’ naïveté. They were caught up in obligations because there was no pop group handbook to navigate the challenges, weigh all offers, or understand their limits. Like all pioneers, the band—and their small team, which contrasts with the intricate machinery that musicians have today for their projects and tours, with McCartney being the best example—paved the way through sacrifice and by doing things so that those who followed wouldn’t have to. We know that this whirlwind would eventually lead the Beatles to a dilemma: continue playing the game by sacrificing creativity, or sticking with music and sacrificing promotional agreements, a gamble they couldn’t afford in 1964; they could, and did, a little over two years later, marking a milestone in the pop world.

It’s understandable, then, that John, Paul, George, and Ringo were exhausted. The psychological burden of fame was something they had already begun to feel, with Harrison being the most vocal on this subject. The world tickled with Beatlemania, but it was at the cost of the four’s nervous systems. This was an existential crisis, where even the most successful person in the world feels like a loser: what is the point of all of this?

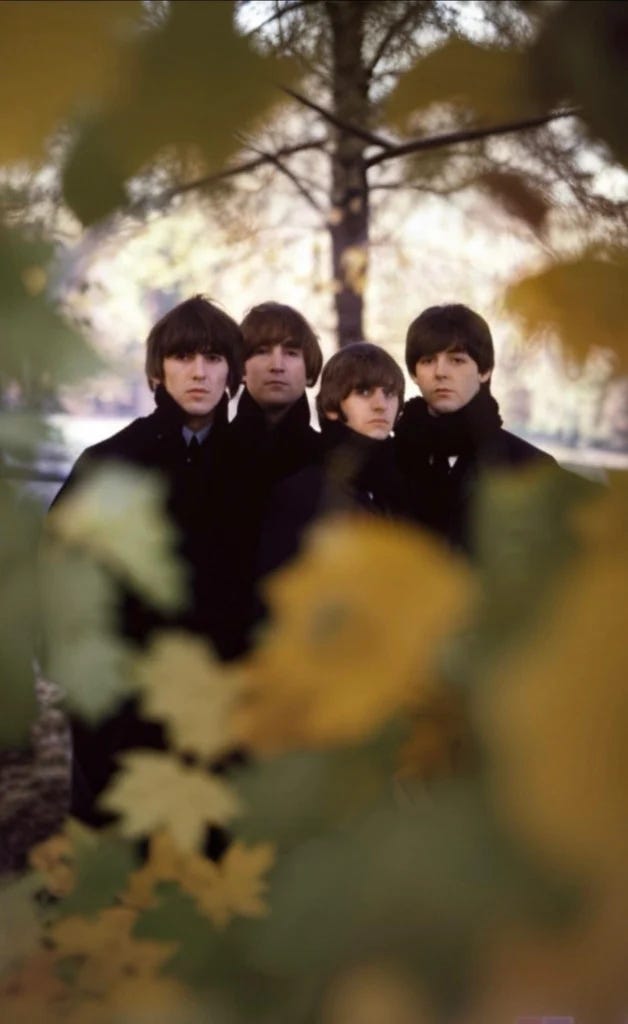

The Beatles’ story is extraordinary in every respect. But, above all, because they always found ways to survive and create. Or, rather, to survive by creating. The cover, a photograph by Robert Freeman taken in a crisp autumnal Hyde Park, shows the four of them visibly fatigued but still there: we’re still standing, they seem to say. They already knew who they were, and nothing was going to stop them.

By 1964, they were the toppermost of the poppermost, bigger than Elvis. But the promises of fame are hollow. They encountered the transactional nature of their relationships, endless hours on airplanes, the back seats of limousines, and hotel rooms all very tiring. For them, music was always the most important thing, but the world didn’t always seem to agree: concerts had become more about watching them than listening to them. There was confusion and frustration. And although they were the brightest pop stars ever known, they were still just pop stars, tied—according to the canonical idea of the time—to a temporary contract with audiences and the industry.

Despite everything, they were where they wanted to be, fulfilling an ambition and seeing the world. In August of that year, they met with Bob Dylan and his entourage at the Hotel Delmonico in New York—heads of two of the era’s most powerful cultural trends. It was a meeting that caused waves. For Dylan, it marked a vindication of his decision to fuse his sounds with electric music and become the rock myth he was destined to be. For the Beatles, besides the validation of marijuana as a means of escape and, above all, inspiration—their meeting took place amid cheap wine and the pervasive smoke of joints—it gave them permission to try to get deeper with their songs. They all were young members of a generation that realized things could be different. In that sense, Beatles for Sale is a sublime representation of the conflict between artistic growth and the public persona they had to maintain at that moment.

This tension is evident in their music, which in Beatles for Sale is, indeed, more languid and somber. More serious. It is, of course, due to their exhaustion. But it is also the result of an evolving process of ideas and sounds. Part of the magic of the Beatles’ story is that their growth happened in public and through their interaction—and openness—to the context around them. They knew how to say yes and take responsibility for the consequences. In any case, introspection is found in their own songs, because the covers are reflections of why they loved the old rock’n’roll: it was their lifeline.

The Beatles are the band of yes. And, in this sense, with everything happening around them, Beatles for Sale is one big, magnificent yes.

In its historical context, Beatles for Sale arrived in a hedonistic and colorful Swinging London. 1964 was an interesting year. The mod culture was reaching its peak, and Englishness was a source of fascination and admiration. British working-class kitchen sink dramas gave way to James Bond films (Ian Fleming died in August). Fashion became a form of youthful expression like never before, and teens stormed society. In January of that year, the Top of the Pops program began airing on the BBC; the pirate station Radio Caroline took over the airwaves in March, the same month mods and rockers fought battles on the beaches of Clacton; by May, the punches would be thrown in Brighton. Beat groups dominated the charts, and the press embraced the new culture, solidifying it as such. Churchill sat for the last time in the House of Commons, marking his retirement, and in October Harold Wilson won the elections, ending 13 years of Conservative rule. Liverpool FC won the league. Peter Sellers married Britt Ekland. And A Hard Day’s Night became the focal point of this new world.

For the Beatles, it wasn’t just Dylan and marijuana. This entire universe aligned with them in a virtuous circle where they gave and received. Their move to London brought them into contact, in one of the world’s capitals, with more creative people—artists, designers, managers, filmmakers, models, other musicians: the pop scene captured in Goodbye, Baby, and Amen by David Bailey and Peter Evans—and they, in turn, transformed the city, making it even more vibrant and stimulating. That December of 1964, Beatles for Sale was simply the latest album from the Beatles, and who knew how much longer the phenomenon would last? As McCartney reveals in an interview for the 2024 documentary Beatles ‘64 directed by David Tedeschi, there was no awareness or intention of making history or changing culture… yet It was just their work, and until then, it had been fun and stimulating.

That December of 1964, Beatles for Sale was exactly what was expected from the Beatles. The critics received it well. The public, of course, bought the record—presented in a beautiful gatefold sleeve—by the ton. The songs flooded the airwaves. And Beatlemania, so intense that year, was preparing to spend Christmas with new music from the four individuals who, step by step, were redefining what it meant to be young.

This brings me to another way of looking at Beatles for Sale as the band's response to the phenomenon and machinery of Beatlemania. With the group exhausted and in the midst of confusion over the media frenzy and the pressure to produce hits, they were already yearning for a different kind of artistic freedom—embodied by Dylan, the London avant-garde, and other collaborators like Richard Lester, director of A Hard Day’s Night—but with the possibility of exercising that freedom within the commercial framework of pop.

They begin to open up to a stylistic variety that would reach its peak in Revolver and become the defining strength of The White Album. This is something they had embraced since their beginnings as a band, and if they had no prejudices against incorporating both rock’n’roll and ballads or musical theater songs, their attempt to harmonize with folk and country music was both natural and a small internal rebellion against their image as teen idols. The two musical elements that nourished this album were of a more prominent seriousness, more closely related to the adult world; on one hand, an intellectual music that explored aspects beyond pop’s domain; on the other, an emotional music with roots that draws from a pastoral melancholy where the first-person perspective is that of the defeated. The fact that the Beatles responded to the cultural zeitgeist with something like Beatles for Sale speaks to a stylistic and ideological challenge that, without compromising their public image, pointed to the direction they would take in 1965 with Help! and Rubber Soul. It was no longer music for feeling good, it was music to expand horizons. It was also a challenge to the expectations of the industry and the public, which took advantage of the inertia of A Hard Day’s Night and Beatlemania to meddle in the very system they were positioning themselves against.

Because we’re talking about a product that fulfills a contractual obligation. But if there’s one thing that distinguished the Beatles from their contemporaries, it’s that they always manufactured with a strong quality control and great attention to detail. As pop fans themselves, they respected their audience as much as they respected themselves.

We know that other things would come for the Beatles and for the world. But, at every step, they were discovering the world and incorporating it into their creativity—such as the feedback at the beginning of I Feel Fine, or the way they approached new emotions in their music—and, at the same time, inventing the world from that same creativity. Beatles for Sale attests, with music as bold as only the Beatles could make it, that creation can emerge from chaos. And that, no matter what, one must always take the next step. The Beatles did. And far they went.

C/S.